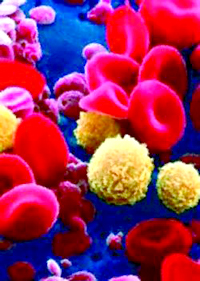

A microscopic look at a lab dish whose contents are derived from human embryonic stem cells

They have been likened to the dot at the top of an “i” and to tiny soccer balls. Some see them as the beginning of life, others as building blocks for medical miracles and still others as medical debris. And while most politicians would be hard pressed to define or spell blastocyst, these tiny bits of matter sit at the center of one of the most contentious policy disputes of our time – the fight over embryonic stem cell research.

Now the fight has come to New York. Ever since President George Bush banned most federal funding for most embryonic stem cell research in 2001, some states have sought to pick up the slack and so entice researchers and possible new industry. New York seems a likely location for this kind of research. Almost 55,000 people in the state work in the pharmaceutical and bio-tech industries, and the city is home to many top research institutions. With the construction of a new bio-tech center on the East Side, the Bloomberg administration hopes many private companies will bring their cutting-edge bio-tech businesses to New York.

To keep New York in the forefront of bio-technology, some members of the state legislature, including most prominently Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, hope to obtain state funding for embryonic stem cell research. On the other side, the Catholic church, which has spearheaded opposition to embryonic stem cell research here, argues that embryos used for stem cell research are a form of human life. The governor, meanwhile, remains somewhere in the middle – in favor of biotechnology in general but reluctant to support embryonic stem cell research explicitly.

As New York continues to mull the issue, some of its neighbors have moved ahead, threatening New York’s future as a center of bio-technology and, some say, delaying the day when sick people will get cures they desperately need.

WHAT IS STEM CELL RESEARCH

Although embryonic stem cells have not yet cured a single disease, it is hard to overstate the hopes that many experts have for them. Supporters of the research liken it to where antibiotics were 50 or 75 years ago. No one knows when, how, where – or even if – the major breakthroughs will come. But said Robin Elliott, the executive director of the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, who also serves as chairman of New Yorkers for the Advancement of Medical Research, “The same could be said of any frontier of medicine…This is an area of science that is potentially one of the most exciting in the history of medicine.”

|

|

The controversy over embryonic stem cell research involves balancing hopes for improving the lives of millions against fears of a Brave New World Society where human beings will be just another manufactured product.

Most embryonic stem cells used by scientists today are a byproduct of in vitro -- literally “in glass” -- fertilization, which has led to the births of hundreds of thousands of babies since 1978. The process involves surgically removing mature eggs from a woman – generally she takes drugs to enable several eggs to mature simultaneously – and joining the eggs with sperm in a laboratory rather than in the woman’s body. The fertilized egg is then implanted in a woman’s uterus where, if all goes well, it will develop into a healthy baby about nine months later.

Women trying to become pregnant through in vitro fertilization often have to undergo several implants before the procedure works. So most women store surplus fertilized eggs, and today thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of these small spherical blastocysts remain in clinics around the country.

For years, there was little use for most of the embryos, and ethicists debated what to do with them. Then in November 1998, James Thomson, a biologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, reported that he had isolated human embryonic stem cells. These stem cells could renew themselves, by dividing again and again. With each division, scientists could create one differentiated cell – a blood cell, say, or a brain cell – and one stem cell, which could then be used to generate more cells. These related cells -– the offspring of the original cell -– constitute a group of cells, which scientists call a "line", that share the same DNA.

To create these lines, scientists have to separate the embryo into individual cells, thereby destroying it. They must then put the individual cell in a dish and provide it with nutrients and growth factors that will both encourage it to divide and create the differentiated cells. According to one count, there are about 240 human embryonic stem cell lines around the world.

Scientists hope the lines’ ability to create specific types of cells will enable researchers to understand a variety of diseases and eventually treat illnesses that entail lost or damaged cells, such as diabetes, some cancers, Alzheimer’s disease, and spinal cord injury.

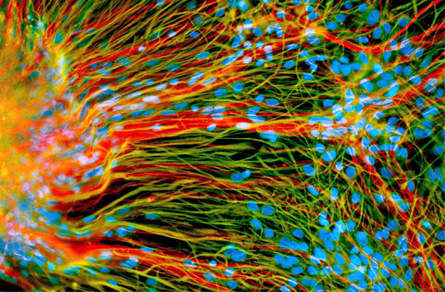

For example, in people with Parkinson’s disease the cells of their brains cannot produce enough dopamine, which is essential to the functioning of the central nervous system. Brain cells created from embryonic stem cells could replace the deficient cells, enabling the patient’s brain to again produce dopamine and the nervous system to resume functioning normally.

This potential for possible cures has won embryonic stem cell research some prominent supporters, including Nancy Reagan, whose husband had Alzheimer’s disease; Michael J. Fox, who has Parkinson’s disease; and the late Christopher Reeve, who was paralyzed as the result of a spinal cord injury.

Since the 1970s, scientists have been studying adult stem cells, extracted from blood and bone marrow, as well as from organs taken from dead bodies. Working with such cells is not particularly controversial, and they are already used in areas such as bone marrow transplants and in treating eye injuries. But these older stem cells may be more set in their ways – scientists differ (in pdf format) over how versatile they might be -- and so unable to develop into some other types of cells. And the supply of these cells, particularly those from donated organs, is limited.

Because embryonic stem cells can keep dividing and renewing themselves for long periods of time, they could exist in greater supply. The problem, though, is where to get them in the first place. For now – and this is where in vitro fertilization enters the picture – most embryonic stem cells derive from blastocysts, several-day-old embryos that have not been implanted in a uterus. And these blastocysts come from in vitro fertilization clinics.

Scientists are trying to develop other methods to produce cells with the properties of embryonic stem cells. But for now, the cells come from embryos that are destroyed in the process.

THE ETHICAL ISSUES

This troubles many people, including leaders of the Catholic Church, members of the Christian right, and some, though certainly not all, anti-abortion advocates. They see the blastocyst as a human life and believe that destroying it – even to save someone from disease — is wrong. “We don’t think a human life should ever be a means to an end,” said Dennis Powst, director of communications for the New York State Catholic Conference. “It’s not an ethical way to go about curing disease.”

To underscore the link between the blastocysts and human life, President George W. Bush last year hailed the birth of 81 children from “adopted” embryos – dubbed “snowflake babies” -- and told a gathering of the families, “There is no such thing as a spare embryo. Every embryo is unique and genetically complete, like every other human being…. These lives are not raw material to be exploited, but gifts.”

The blastocyst legally belongs to the family that created it. A small number of these families turn their embryos over for adoption or for more medical research. But most of the embryos are now simply destroyed. Supporters of stem cell research argue that using the blastocysts to help find a cure for debilitating diseases would be far more ethical than just throwing them away.

Opponents of embryonic stem cell research also fear that the need for a steady stream of stem cells for research and treatment could lead scientists to try to create human embryos by cloning. “If cloning is not part and parcel of embryonic stem cell research,” said Powst, “we question why human cloning research is part of every bill” supporting embryonic stem cell research.

While most advocates of stem cell research say they oppose cloning for reproductive purposes they do support so-called “therapeutic cloning.” In this procedure, the nucleus of an adult cell is placed in an unfertilized human egg. Development would advance until the egg became a blastocyst but, advocates say, could go no further. There is, they stress, no way such an egg could ever become a human being.

THE POLICY HISTORY

In 2001, the Bush administration came down on the side of those opposing embryonic stem cell research. The federal National Institutes of Health said that it would only fund embryonic stem cell research using existing, self propagating lines of cells. But many of those lines turned out to be contaminated, leaving less than two dozen available for research. No federal money could go to create new lines.

In 2001, the Bush administration came down on the side of those opposing embryonic stem cell research. The federal National Institutes of Health said that it would only fund embryonic stem cell research using existing, self propagating lines of cells. But many of those lines turned out to be contaminated, leaving less than two dozen available for research. No federal money could go to create new lines.

The move did not ban embryonic stem cell research, but since the National Institutes funds most medical research in this country, particularly in areas where commercial applications remain years away, the action had quite an impact. “It’s mind boggling to researchers that the federal government has taken this action,“ said Maria Mitchell, president of AMDeC Foundation, a nonprofit consortium of New York medical schools and health care and research organizations.

The federal action discourages “an entire generation of young scientists from even going into the field,” said Susan Solomon of the New York Stem Cell Foundation. NIH bars research institutions from using any federally funded facilities for embryonic stem cell research. ”It’s a kind of McCarthyite environment,” Solomon said. “There’s a potential that since NIH is an executive branch creation that someone could come in and withdraw federal funding” from a lab doing work with embryonic stem cells.

Other countries, including England, South Korea and China, have continued to push ahead. And in the United States, individual states have begun to try to fill the void left by the national government. “Washington dropped the ball in our view. That’s the only reason this is coming up,” said Elliott.

In 2004, California passed a referendum, setting up its own agency that could provide $3 billion over the next 10 years for embryonic stem cell research. So far no money has been handed out because the measure is being challenged in court. Other states, including New Jersey and Connecticut, also have moved to provide money for stem cell research.

NEW YORK AND STEM CELL RESEARCH

A Hub for Research

In many respects, New York City seems a promising place for stem cell research. It is home to 49 teaching hospitals, eight major medical schools and eight medical institutions that are among the top 80 recipients of NIH research funds, according to a 2002 report by the Center for an Urban Future.

“New York is blessed with a real wealth of bio-medical research institutions and talent, “ said Ross Frommer, a spokesman for Columbia University Health Sciences. “Cutting edge research should be done at a place that’s good at doing cutting edge research.”

The Bio-Tech Business

Even though any commercial application of stem cell research is years, if not decades away, many leaders in medicine and research say the state cannot afford to be left behind. If New York does not fund stem cell research while its neighbors do, the state will lose the best scientists, research funds and, eventually, commercial opportunities. “In one word, it’s competition,” said Mitchell. “Not being involved in one of the most promising areas of research would put us at a huge disadvantage.”

If New York is seen as less than friendly to medical research, the state could lose out on more commercial aspects of bio-technology as well. Today biotech and pharmaceutical companies together employ almost 55,000 people in the state and pay $3.3 billion in wages, according to the New York Biotechnology Association. But New York State, and particularly the city, have lagged behind other areas in attracting commercial bio-tech jobs. In the past decade, says Maria Gotsch, of the Partnership for New York City, a business group, that situation began to change.

The City’s Effort

Both Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and Michael Bloomberg tried to attract bio-tech to the city. As part of that, the city is moving on the East River Science Park in Manhattan, which will provide 870,000 square feet of lab and other space for start-up bio-tech companies. In the past, businesses have cited the real estate crunch – and the lack of laboratory space at any price -- as impediments to bringing bio-tech jobs to the city. “There’s no lab space because there’s no industry and no industry because there’s no lab space,” Gotsch said. “We believe the project will provide the critical mass to get the industry going.”

The first two buildings should be complete and open for business by 2008. According to Gotsch, the project is expected to create 4,000 construction jobs and, when complete, 2,000 permanent jobs.

The state has also worked to attract bio-tech, although most of its programs have been focused outside of the city. But without support for stem cell research, such efforts could be for naught. The state has put money into technology and now is in a position to see the benefits of those investments said Robin Gelburd, general counsel for AMDeC Foundation. But, she added, “a failure to move with stem cell research would be an impediment to reaping those seeds.”

The Private Effort

Even without federal or state money, embryonic stem cell research is taking place in New York, much of it funded by foundations and individual donors. Using private money, Weill Cornell Medical Center hopes to launch a facility to develop and maintain embryonic stem cells for research. Memorial Sloane Kettering Cancer Center investigators are studying whether embryonic stem cells could some day repair damage caused by radiation treatment for brain tumors. A Columbia University embryology professor seeks to learn how cells taken from embryos would behave in adults. At Mount Sinai, The Black Family Stem Cell Institute hopes to use findings about embryonic stem cells to develop new therapies for degenerative diseases.

“The private money is absolutely very, very welcome,” said Elliot. “But private money is never going to be enough.”

Looking to Albany

And so supporters of embryonic stem cell research want the state to become involved. In November, New Yorkers for the Advancement of Medical Research urged Governor George Pataki to include $100 million for stem cell research in his budget for the next fiscal year. And earlier this year, leaders of 17 research institutions in the state called on Albany to establish a fund to support stem cell research. “If New York fails to act, we risk losing our place as one of the leading, if not the leading, location for biomedical research,” the study said

Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, who proponents say has been a champion of stem cell research, has proposed a bill that would provide $300 million in state funding for stem cell research, including embryonic stem cell research, between now and June 30, 2007. The bill passed the Assembly last year but stumbled in the Senate. The Assembly approved it again this year.

In his State of the State speech, Governor George Pataki called for a bio-tech initiative that he said could generate $800 million in public and private funding. It might finance stem cell research and then again it might not. The plan does include a bio-ethics board that that would provide guidance on “ethical, moral and public policy issues” arising from the proposed projects. That panel could be “a wonderful thing,” said Robin Elliott, but it could also be “a veiled fist for an ideological agenda.”

Although a spokesperson for the governor said last year that he is “supportive of the concept of stem cell research,” Pataki has not spoken out explicitly for it. But deadlocks between Silver and Pataki are a familiar story in Albany and one that often leads to nothing being done at all. Silver said that Democratic gubernatorial candidate Eliot Spitzer supports his bill but Spitzer’s office has not confirmed that.

Meanwhile, Mayor Michael Bloomberg donated $100 million to Johns Hopkins University, with the apparent understanding that much of it would go for embryonic stem cell research.

Opponents says that, instead of focusing on embryonic stem cell research, the state should support adult stem cell research and make effort to collect and use umbilical chord blood, said Powst. “They’re providing benefits now, but embryonic research is still a theoretical proposition,” he said.

But stem cell proponents worry that, without a specific provision for the research it could get lost among hundreds of competing – and worthy – demands. And, because of the federal ban on funding embryonic stem cell research, they say the state must step in. “Stem cell research is an area where there’s a real void in federal funding,” said Ross Frommer from Columbia University. “Somebody has to step up and fill that void.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Organizations and web site

Do No Harm

A coalition supporting medical technologies that do not involve destruction of human embryos, the group advocates adult stem cell research.

New York Biotechnology Association

A trade association that advocates development and growth of New York State based biotechnology related industries and institutions

New York State Catholic Conference

The position on embryonic stem cell of this group, which represents the state’s bishops on public policy issues.

New York Stem Cell Foundation

A non-profit organization dedicated to furthering human embryonic stem cell research to advance the search for cures of the major diseases of our time.

New Yorkers for the Advancement of Medical Research

A coalition of New York State-based disease advocacy groups, university research centers and biotech industry leaders that have assembled to lead a charge to achieve legislation that would affirm and support scientific research involving embryonic stem cells and other DNA therapies

Reports and Articles

“The California Stem-Cell Gold Rush” (New York Magazine)

New York risks losing its best scientific minds as well as billions of dollars to other states that are investing in stem cell research.

New York and Stem Cell Research

A report by leaders of 17 state research institutions analyzing the scientific, therapeutic, and economic issues related to stem cell research in the state and calling for the state government to fund more research.

The Stem Cell Debate (Boston Globe)

Pulitzer Prize winning coverage of many aspects of the issue.

Stem Cells: Scientific Progress and Future Research Directions (National Institues of Health)

A review of the state of the science of stem cell research as of June 17, 2001. Included in this report is subject matter addressing stem cells from adult, fetal tissue, and embryonic sources.

Â