|

Also: Related in Community Gazettes:

|

Unlike most New Yorkers, Carl Van Putten and Lilian Garcia pay attention to garbage after it is thrown away. They have little choice: their neighborhood, Hunts Point, is home to many of the city's "waste transfer stations" - sheds where garbage trucks dump trash so that larger trucks can pick it up and carry it out of state.

"The minute I came to Hunts Point my son developed chronic asthma," said Garcia.

On any given morning, as many as ten garbage trucks stand idling within a block of Van Putten's home on Hunts Point Avenue, where the breeze sends the smell directly towards him.

"I don't have polite words for it," he said. "You can call it a fragrance, aroma, or odor, but it's still a stink. It's heavy."

That is why they were happy to learn of Mayor Michael Bloomberg's solid waste management plan (pdf format), which would move most of the 50,000 tons of trash the city produces each day by rail or barge, instead of by truck. [For more about the plan's effect on the South Bronx, read Dumping Ground No Longer?in the Community Gazettes for the South Bronx].

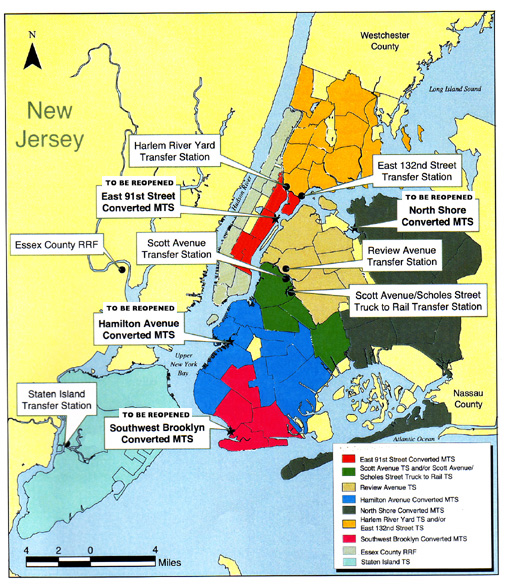

To do this, Bloomberg proposes to reopen four city-owned marine transfer stations, piers where trucks can dump trash onto barges, to handle the city's residential waste. The proposal is the third in a waste management plan that the mayor has rolled out over the last month:

- Recycling - The city signed a 20 year contract with Hugo Neu, a recycling company that will build a recyling station on the Brooklyn side of the East River.

- Commercial - A transfer station on 59th Street on Manhattan's West Side, is to be reopened to handle the city's commercial waste.

- Residential - Four transfer stations are to be reopened for residential garbage, one on Manhattan's Upper East Side, one in College Point, Queens, and two in Brooklyn (one in Red Hook and one in Gravesend).

The stations that the mayor wants to reopen were closed when the city stopped using Fresh Kills landfill on Staten Island in 2001. Whether these stations handle commercial waste or residential waste doesn't matter much to those people who live near the stations; some don't see why the burden should now be placed on them.

"I know that the garbage has to go someplace," said Sandy Whitlock, who lives near the transfer station on the Upper East Side. "But it shouldn't have to impact a residential community." [For more, read The Garbage Returns to the Upper East Side in the Community Gazette].

Aside from complaints on the neighborhood level, some say the plan doesn't do enough to address the citywide trash problem. The prices the city pays to move its trash have risen substantially since Fresh Kills closed. Some out-of-state landfills that the city uses are nearing capacity, and the states where these landfills are located are often not much more interested in receiving the city's trash than are residents of the South Bronx.

Despite this, what the mayor describes as his comprehensive waste management policy stops at city limits, a shortcoming that experts like Benjamin Miller, former director of policy planning for the Department of Sanitation and author of the book Fat of the Land: Garbage in New York the Last 200 Years, see as its major flaw. [Read Miller's analysis, "The Waste Management Plan: Approve It, But Improve It"].

"The most important thing is where this stuff goes," Miller said, "and there's been no talk of that."

BURYING IT, BURNING IT, DUMPING IT

The challenge of dealing with garbage is not a new one to New York City. The city has long searched for an effective way to manage its waste - piling it onto islands, carting it to far-off lands, selling it to entrepreneurs, feeding it to hogs, burning it, or simply dumping it into the sea. Trash has been used as the foundation for airports, parks, and beaches. People trying to keep it from being shipped to their communities have proposed legislation and gotten into fistfights at City Hall to further their cases.

Many ambitious plans to manage the city's waste have not become anything more than words on paper. One supposedly temporary one, though, ended up turning into the largest manmade object on the planet.

When Fresh Kills landfill opened in 1947, it was slated to close within three years. Instead, it became the center of a citywide system that lasted until 2001. Sanitation Department trucks that collected residential waste and privately owned trucks that collected commercial waste would travel to one of eight marine transfer stations, where they would be emptied onto barges headed for Fresh Kills.

In the mid-1980s, the city raised the price of using these piers, and private companies built their own smaller truck transfer stations in places like the South Bronx and Northern Brooklyn. Trucks carting commercial waste transferred garbage to others headed out of state at dozens of these facilities. The city's residential waste, meanwhile, continued to go by barge to Fresh Kills.

In 1996, however, Mayor Giuliani pleased the Staten Islanders who made up an essential part of his political base by announcing that he would close down Fresh Kills. Consequently, the city-run marine transfer stations essential for the barge system were closed.

But by ending the Fresh Kills era without planning for the next, Giuliani left the city's own trucks with nowhere to go.

AFTER FRESH KILLS

The Sanitation Department began sending its trucks to the private transfer stations, where the trash they carried was dumped - or "tipped" - and reloaded, sometimes onto a train but usually onto a truck, and shipped out of state.

Private companies built these facilities based on their own business decisions, and the burden fell disproportionately on several neighborhoods. In a recent report (in pdf format), Environmental Defense, a national environmental group, found that 80 percent of the waste handled by private waste transfer stations goes to four of the city's 59 community board districts. "You have right now these stations located in neighborhoods where probably the land value was lower and the zoning was different. When [private companies] looked to set up those stations, [they] looked for those things," said Ramon Cruz of Environmental Defense. "Is that fair? No, but it's a function of the market."

The hundreds of trucks moving through these neighborhoods every day were not just smelly. Their weight took its toll on the roads, and their exhaust polluted the air. Asthma rates skyrocketed in areas where the stations were concentrated, a health effect linked directly to the garbage truck traffic.

Nor was this system particularly healthy for the city's economy. Shipping trash to landfills in Virginia or Pennsylvania was much more expensive than floating it to Staten Island. The per-ton contract for shipping garbage rose from $54 in 1997 to its present price of $74, a 40 percent increase over seven years. (If increased gas and labor prices are factored in, the increase is even larger.) The Department of Sanitation budget ballooned. Private companies saw their prices rise 50 percent over the same period.

Additionally, other states have resisted the city's garbage by imposing surcharges on out-of-state waste, and have passed laws to limit importation of trash. Federal legislation with the same goal has been introduced several times; there is currently legislation pending in both the House of Representatives and Senate.

To date, these laws have been overturned or rejected because they violate interstate commerce regulations, but they indicate the city's continuing vulnerability to events that are out of its control.

These problems are not secrets. But largely because any change in garbage policy alienates one political constituency or another, the city has faltered without a plan for years.

THE MAYOR'S PLAN

Over the last several weeks, Mayor Bloomberg has announced several proposals that, he says, add up to a comprehensive plan for dealing with garbage. The common element of his three plans is to shift from using trucks towards using barges and rail to move garbage out of the city.

To do this, the mayor intends to reopen four of the marine transfer stations that were closed along with Fresh Kills to haul the city's residential waste. Another station will handle the city's commercial waste.

The city's recycling will also be shipped via barge. The city will reopen a station at Gansevoort Street in Manhattan's meatpacking district, from which the recyclables will sail to a facility being constructed by scrap-metal company Hugo Neu in Brooklyn. The city also hopes to increase the proportion of its waste that gets recycled, to 25 percent of residential garbage by 2007 and then to 70 percent of both residential and commercial garbage by 2015.

The mayor has calculated that his plan to reopen the marine transfer stations for residential garbage will reduce truck traffic in the city by almost three million miles a year. This will have an obvious benefit for the city's roads; it will also reduce gas and labor costs and ease the environmental burden of waste management.

The city can count on its own trucks bringing residential waste where it would like. It cannot, however, simply force private companies to do the same with commercial waste. The Economic Development Corporation and the mayor's office are in the beginning stages of developing a system of incentives and regulations that will make its transfer station more attractive, while also raising the costs of running private transfer stations.

|

|

Clashing Communities

If the city can significantly reduce the use of private transfer stations, the negative effects of moving trash out of the city will be spread much more evenly, and the overall impact on the environment will be reduced. Community organizations and environmental groups that have long been calling for such changes are reacting positively to the idea.

Rare is the garbage plan that does not create resistance from those areas that will receive a larger burden, however, and this plan is no exception. Residents and local officials from the Upper East Side, represented by the mayor's chief political rival, Council Speaker Gifford Miller, object to the reopening of a station in their neighborhood. They say that the station's proximity to such a dense residential neighborhood is reason to keep it closed.

Miller makes a familiar argument: what is unhealthy in one neighborhood shouldn't be allowed in another. The Bronx and Brooklyn have used the same argument in their calls for Manhattan to handle it own trash; Staten Island periodically threatened to secede for decades, its residents' aspiration to become a separate city inspired largely by the feeling that the rest of New York was dumping its trash on their borough.

Bloomberg is unconvinced that the Upper East Side will suffer unfairly. "Every single part of this city has to participate in solving a very difficult problem," he said in response to Miller's objection, adding that the East Side produces a fair amount of residential trash and the facility already exists. "Nobody wants to have solid waste near them, but somebody's going to have to ... [Y]ou are limited to where you can site facilities."

While the mayor insists that politics did not fit into his decision to open this particular station, he does seem to have set up a political confrontation that could work to his advantage - hardly a rare move for politicians dealing with New York City's garbage.

An Expensive Plan With Dubious Economic Benefits

Bloomberg estimates that opening the marine transfer stations will cost $340 million, $85 million each. The total investment is actually larger, since the price of revamping the station for commercial waste or the operating expenses of these facilities are not included in this figure. (The recycling plant, on the other hand, is being built by Hugo Neu at no cost to the city; the contract by which it will handle the city's recycling is estimated to save $20 million annually).

The proponents of the plan are not promising a miraculous reduction in cost, though.

"It's not going to get cheaper; let's not kid ourselves," Sanitation Commissioner John Doherty said at the press conference where the details of the plan were announced. "What [this plan] is going to do is stabilize the costs."

But critics question whether it will even do that. A few large companies already run the waste management industry. According to the city Comptroller's office, 91 percent of the trash headed for landfills is controlled by one of three companies. Since a limited number of facilities can accept trash from barge or rail, the city may be making itself even more vulnerable to an uncompetitive market by relying solely on these two forms of transportation.

This problem underscores what critics say is a major weakness in the city's new plan: a failure to figure out where the garbage will go after it is shipped out of the city.

WHERE OUR GARBAGE GOES

The plan in its current form carefully itemizes how trash from each borough will leave the city. But the most distant destination it mentions is the Essex County Resource Recovery Facility, an incinerator in Newark New Jersey that converts a good portion of Manhattan's waste into energy. Newark is about 12 miles from midtown. But almost half of the 15 million tons of waste the city generates each year is sent to landfills in either Virginia or Pennsylvania, with some trucks driving as much as 1,300 miles roundtrip.

These trips are expensive, and are bound to get more so as gas prices rise, the landfills in other states fill up, and states continue to look for ways to keep New York City garbage out.

The effort of other states "is not slamming the door completely, but it's making the doors smaller, and it's making the price higher," said Benjamin Miller. "That's going to keep happening forever, and the only way to solve that problem … [is] to have a landfill in New York State."

The city comptroller's office agrees. In a report published this month (in pdf format), it advocated an in-state landfill. Although communities often don't want landfills, dumps do bring economic benefit, the report argued, and it makes sense to have that economic benefit go to New York State. In addition, a landfill in New York State that the city itself controlls would shield it from the anti-importation regulations in other states, and might even curb the enthusiasm to pass such laws.

For their part, the mayor's office and the Sanitation Department say that they sent a query (in pdf format) to upstate communities earlier this year asking them to consider a landfill for New York City waste and received no responses. Critics say the lack of interest is a result of a request so vague that it was impossible to take seriously.

WILL THE LATEST PLAN BE IMPLEMENTED?

Even under the best of conditions - if the City Council approves the plan, and the revamping of the now-closed stations goes according to schedule, and the commercial carters agree to use the city's facilities instead of their own - the new system will not be in place until 2007.

But plans dealing with garbage in New York City rarely enjoy the best of conditions. Big ideas tend to emerge, meet public resistance, fade away, and then sometimes re-emerge years or even decades later. Mayor Bloomberg himself announced a plan to reopen all eight marine transfer stations two years ago that quickly disappeared; Mayor Giuliani's comprehensive plan for garbage similarly vanished. Burning garbage used to be commonplace, but after spending a good deal of the 1990s planning for an incinerator at the Brooklyn Navy Yards, city officials now consider such facilities unspeakably bad ideas.

One big reason for this inability to latch onto a permanent solution, some say, is the public attitude. New Yorkers do not want to take responsibility for their own garbage. This helps explain, anthropologist Robin Nagle has pointed out, why sanitation workers might as well be invisible. They know more about any city neighborhood "than the most sophisticated sociologist just by observing what it discards," Nagle wrote in a recent online diary about her experiences working alongside NYC sanitation workers, "but no one [cares] about their insights. In fact, no one [cares] much about them at all."