When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

When Mayor Michael Bloomberg announced last month that New York City's fiscal crisis was beginning to subside, he hailed the "heroes of this crisis" and said it was time to reward those who helped "get us through the last two years."

But the "heroes" the mayor was talking about were not the police who saw their ranks decline by 4,000 officers nor the firefighters who worked to cover more neighborhoods after six firehouses closed - but taxpayers who own their own homes.

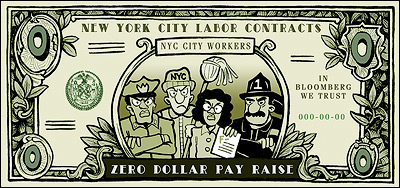

In his $45 billion budget, Mayor Bloomberg proposed a $400 property tax rebate for condo, co-op, and homeowners, but he said there was no money for pay increases for city employees.

"People will look and say there's lots of money in there for raises," the mayor said. "There isn't."

Every city labor union contract has expired, but Mayor Bloomberg says there can be no salary increases without concessions on work rules, benefit packages, and overtime and vacation policy. So far, the City Council, which has traditionally championed city workers, agrees with the mayor, and even offered to give out larger tax breaks rather than advocate for raises.

Labor leaders accuse officials of playing political games with the budget and ignoring the workforce that keeps the city running.

"Now is the time to invest in our public employees who have not let us down," said Brian McLaughlin of the New York City Central Labor Council. "Years of privatization and productivity schemes from City Hall have gotten us nowhere."

The outcome of these contentious negotiations between city government and labor have an impact not only on the city's fiscal health, but also on how the schools run, how clean the streets are, if crime goes up or down, and how long it takes to put out a fire.

THE CITY'S WORKFORCE AND COSTS

New York City employs about 286,000 full- and part-time workers. The full-time workforce is often divided into three categories:

- 96,000 teachers

- 64,000 uniformed employees - police, firefighters, corrections officers, and sanitation workers

- 80,000 "civilian" employees - all of the workers that do not fit into other categories.

In the last three years, in an effort to streamline government and cut costs, the city's workforce has decreased by 5 percent or 14,000 full-time positions.

But despite cuts, the city's overall labor costs have risen 20 percent.

The reason, say fiscal watchdogs, is that New York's overtime, benefit and pension packages are more expensive than elsewhere in the country and the costs continue to rise.

In 2003, New York City paid out $870 million in overtime, nearly double the total a decade ago. The average cost of a New York City worker is now more than $82,000 a year, including pay and benefits, according to one report (in pdf format).

"A significant part of the city's budget problem is caused by growing personnel costs," said Diana Fortuna of the Citizens Budget Commission. "The city will be continually forced to cut services if these costs are not curtailed."

In addition to the city's active workforce, New York also supports 180,000 people who have already retired.

Pension costs are the fastest rising share of the budget. According to the mayor's office, pension and fringe benefit costs rise 5 percent each year; by the year 2008, the city will pay $10 billion a year in pensions or about 20 percent of the annual budget.

WHAT CITY HALL WANTS

Since he took office in January 2002, Mayor Bloomberg has taken a fairly tough approach toward unions.

The mayor reduced the city's workforce. He threatened to jail MTA workers if they went on strike in December of 2002. And last year, he demanded $600 million in concessions from unions to help balance the budget, when they did not produce what he wanted, he blamed union leaders for tax hikes and service cuts.

"When you do something and help us, then afterward, you can get it back," the mayor told labor leaders.

The mayor's latest budget also proposes a new pension level for city employees that would apply to new employees. It would reduce cost of living adjustments, increase the age and service requirements, and require 10 years of work for city workers to become fully vested in the program. Such a program could produce a total of $10 billion in savings for the city between now and the year 2025, according to City Hall.

The New York City Council, which has no direct role in collective bargaining agreements, but must still approve the budget, generally agrees with the mayor, and has made tax cuts a priority.

"All city employees could use a raise, but unfortunately we are still in some financially difficult times," said Councilmember Joseph Addabbo, Jr., chair of the council's civil service and labor committee.

The City Council also has the power to bring certain labor issues into public view and help shape the negotiations - either by raising workers complaints or uncovering inefficient work rules.

Last fall, Councilmember Eva Moskowitz, who chairs the education committee, held a series of hearings on school employee work rules and helped bring to light how difficult it is to get rid of poorly performing teachers, a process that can sometimes take up to two years.

The union was angered by the council hearings, especially since the overwhelmingly Democratic members usually side with unions in disputes with the mayor. Still shortly after the hearings, the United Federation of Teachers released a plan to overhaul the disciplinary system for teachers, including calling for a task force of pro bono lawyers to clear the backlog of 200 teachers who still receive full pay while awaiting dismissal.

WHAT THE UNIONS WANT

While the mayor can point to rising costs and budget problems, city workers say new contracts and pay raises are long overdue.

Every city union contract - for teachers, police, firefighters, sanitation, corrections, and other workers - has expired. While this is not unusual and new contracts are agreed to retroactively, many workers feel abandoned by the city at a time when taxes, subway fares, and housing costs continue to rise.

Teachers

In June 2002, Mayor Bloomberg negotiated a new contract with teachers that his predecessor Rudolph Giuliani had put off. It included raises of between 16 and 22 percent depending on experience in exchange for working 100 extra minutes a week.

However, since then, relations between City Hall and the United Federation of Teachers have turned contentious.

Recently, the mayor proposed replacing the current 42-year-old, 200-page teachers' contract with an 8-page document that gives the city unprecedented control over educators and the classroom. Bloomberg's teachers contract would:

- Add more days to the school year.

- Bar teachers from doing union work during the school day.

- Eliminate sabbaticals teachers.

- Cut the number of unused sick days that can be cashed in by retirees.

- Give bonuses to teachers to work in low performing schools.

United Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten rejected the proposal and called it a "kick in the teeth."

However, teachers say it is not just about the details of work rules, but giving teachers the respect they deserve. The mayor, they argue, is making it more difficult to recruit and retain quality teachers.

Forty-five percent of all New York City teachers either quit the profession in their first five years or leave for a teaching position outside the city, according to the union. Currently, New York is having an especially difficult time recruiting math and science teachers. The poorest schools have the highest teacher turnover rates, which means those students are put at a further disadvantage.

Uniformed Workers

Contracts with uniformed services - police, firefighters, corrections, and sanitation worker - often follow a pattern; if one union gets a new contract, the others get agreements on a similar scale.

New York police officers, whose contract expired in July 2001, have long been seeking pay that is equal to officers in other places. The starting salary for a New York City police officer is $36,878, compared to $47,853 in Yonkers.

Like teachers, police officers say it is difficult to recruit and retain officers who can make much more in the suburbs. Police officers also stress the danger of their work - risking death while working for the city. In January, the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association unveiled a massive billboard near Times Square that read: "NYC Cops, ranked #1 in the nation in fighting crime - ranked #145 in the nation in salary: It's time to fix the injustice."

Last year, the city tried to broker a deal with correction officers union and its 9,000 members by creating longer shifts, but the deal fell apart when the city wouldn't put the money saved into pay increases. Like the police, correction officers point to the stressful and dangerous nature of their work.

"You want me to turn this entire municipal work force into a slave organization," said Norman Seabrook, president of the Corrections Officers Benevolent Association. "I don't think so."

In many ways the New York City Fire Department is still trying to rebuild the department after they lost 343 firefighters and a combined 4,000 years of experience on September 11, 2001. Last year, the city closed six firehouses in an effort to save money in the budget. Last week, the mayor agreed to increase the number of firefighters from four to five on additional engines. Union officials maintain that increased staffing is critical for ensuring the safety of firefighters and city residents.

"The difference between a five-man engine and a four-man engine is dramatic," said Stephen Cassidy of the union. "It actually takes twice as much time for a four-man engine to get water on a fire."

And the sanitation workers were angered when 217 workers were laid off for budget cuts. Those workers have now all been rehired and workers say they deserve raises and a new contract, which expired in October 2002.

Civilian Workers

City workers represented by District Council 37, which is the city's and the nation's largest union with over 125,000 members, feel particularly abandoned by the city.

The union includes many lower paying jobs like city lifeguards, traffic employees, museum employees, custodians, social workers, and health care workers. The average District Council 37 member makes $29,000 a year, according to a union spokesperson.

"Many are raising families on this salary and having trouble making ends meet," said Lillian Roberts of District Council 37. "With transit hikes and higher taxes, everything has been raised but their salaries. We urgently need a fair contract now."

Union leaders also point out that when the mayor praises city government as being more efficient, it is the everyday workers that are making it happen.

COMPROMISES AND CHALLENGES

There have been some agreements that demonstrate that the mayor and the unions can negotiate when they want to.

In December, both sides reached an agreement on health benefits. City workers and retirees will now pay on average $200 more in out-of-pocket health expenses each year. In return, the city agreed to increase its contribution to a fund for cancer, asthma, and drugs.

Both sides called it a "win-win" agreement: the city saved $100 million and union members preserved their benefit packages. Labor leaders also said that it might be a major step in moving toward new contracts.

But as workers go longer without new contracts and raises, the tension between city government and unions grows.

In New York City, city workers are not legally able to strike, so protests, work slowdowns, and sick outs are options for disgruntled workers. These actions can translate into poorer performing schools, dirty streets, and eventually less money for city services.

It is often an election that gets the city and unions to sit down and negotiate.

Right now, many union leaders are faced with a dilemma: negotiate with the mayor or try to oust him in hopes of getting someone more sympathetic.

In a recent letter to members, Weingarten said that there was a "window of opportunity" to negotiate a new contract before Bloomberg's 2005 reelection campaign, but she said she has grown more pessimistic in recent weeks.

Mayor Bloomberg, who was elected without union support in 2001, has told labor leaders that he plans on being around for a while.

"Anybody that wants to bet that I'm not going to be around in two years and they'll wait it out, that's a pretty stupid bet, if you think about it," the mayor has said. "I'm going to get re-elected."

#####

RELATED ARTICLES

School Contracts: Do They Serve Students? (January 2003)

Police Pay: What Is Fair? (September 2002)

Labor and the New Workplace (June 2002)

Labor's Bill Comes Due(January 2001)

LINKS

City Office of Labor Relations

United Federation of Teachers

District Council 37

New York City Central Labor Council

New York City Police Benevolent Association

Uniformed Firefighters Association