Outside the New York Stock Exchange Outside the New York Stock Exchange |

When the mayor and the governor held a press conference last week at the New York Stock Exchange, they promised a “bold vision” for a “new financial district.” At first glance, what they announced seemed neither bold nor even much of a vision. They presented plans to repave some streets outside the exchange, replace temporary concrete barricades with permanent fences and remove the parked pickup trucks that have been serving as makeshift safety barriers at several downtown intersections.

Even the timing of their press conference – the day before Thanksgiving – seemed to be saying: This is no big deal.

Modest as the plans seem, however, they were a welcome holiday gift to the business leaders and merchants of Lower Manhattan. Wall Street has been clamoring for officials to do something about the stifling security measures that have impeded traffic for more than two years; the complaints began while the twin towers were still burning.

If the streets outside the New York Stock Exchange are undergoing cosmetic changes, the changes happening inside the colonnaded marble building at Broad and Wall Streets are the most dramatic since the Great Depression.

After a series of scandals, the exchange in September named a new director, John S. Reed, who has set about trying to restore public confidence by completely restructuring the institution.

But even some of the exchange's biggest customers are questioning its very nature, suggesting that its time-honored trading floor, and the jobs it generates, be replaced with an electronic system similar to that used by fast-growing NASDAQ.

For New York City, the stakes are especially high. By thoroughly restructuring itself, the exchange is attempting to preserve jobs while retaining its primacy among stock markets and its position at the epicenter of the financial services industry. This industry is arguably the most important in New York, one that accounts for a third of the city's economy and a quarter of its tax revenues.

Even without the recent stock market scandals, New York's position as financial capital has been eroding. In the year 2000, the securities industry in New York City employed 189,000 people; a year later, thanks to the economic slowdown, the figure was down to 175,500. In 1991, the city had just over 30 percent of the nation's securities-related jobs. A decade later, thanks to the rise of electronic stock trading, the figure was below 24 percent. And this was before September 11th, 2001.

When the exchange threatened to leave town and move to New Jersey, city and state officials were quick to offer more than a billion dollars to keep it, promising new headquarters across the street from the current location.

The plans for the new exchange were scrapped after 9/11. Perhaps it is a sign of an era of lowered expectations that, instead of the Giuliani-era press conference announcing a billion-dollar subsidy, the one last week touted changes to the landscape that would cost a total of just some $10 million, paid for by the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. In both cases, though, officials were communicating much the same message: Something must be done.

The New York Stock Exchange, says William Freund, its former chief economist, is facing not just temporary turmoil but a future of ever-greater competition. "I'm confident that it is going to prevail as an institution,” says Freund, now director of the Freund Center for the Study of Securities at Pace University. “But increasingly it will be a very tough fight."

CRISES

Departing New York Stock Exchange chief Dick Grasso, who leaves amid amid revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest. Departing New York Stock Exchange chief Dick Grasso, who leaves amid amid revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest. |

The New York Stock Exchange has weathered many crises since 1792, when a group of traders met beneath a buttonwood tree on Wall Street and formed a loose association that grew into the world's most powerful financial market.

Recent times, however, have been especially difficult. The dotcom bust, revelations that star analysts touted questionable stocks to boost their firms' investment banking businesses and the collapse of such high-flyers as Enron, Worldcom and Tyco shook investor confidence and tainted the investment industry.

This summer, scandal hit the exchange itself after revelations that New York Stock Exchange chairman Richard Grasso was awarded a $187.5 million pay package by a board of directors that he essentially controlled. One particularly irksome item was the $5 million bonus Grasso received for getting the exchange up and running after September 11, 2001. Thousands of others on Wall Street worked tirelessly at the time without any extra compensation.

Though Grasso is widely credited with preserving the New York exchange's share of the market for stocks, during his tenure the exchange developed a reputation for being a vast insiders' playground. His departure unleashed revelations of possible trading abuses and conflicts of interest at the exchange and elsewhere in the financial industry, including a series of investigations by New York State Attorney General Elliot Spitzer that further tarnished Wall Street's image.

UNLIKELY RADICAL

To replace Grasso the exchange tapped as interim chairman the 64-year-old Reed, a former Citicorp chairman known for his fascination with organization charts and information systems.

Coming back from the island off the coast of France where he had comfortably retired, Reed got right to work and declared that he would take a hands-on approach. He set about completely revamping the exchange, making its operations more transparent to both investors and regulators.

"I am a revolutionary," Reed told London's Financial Times in a November 13 interview, his first after taking over.

Reed proposed sweeping changes in the way the exchange is governed. In place of its 27-member board, he called for creating two panels. An eight-member board intended to be independent of the exchanges' management would be responsible for governance and regulation. A second "board of executives," with 20 members drawn from Wall Street firms, specialists and others in the securities industry, would oversee day-to-day operations.

"I am a revolutionary," John Reed told London's Financial Times. "I am a revolutionary," John Reed told London's Financial Times. |

Reed's plan was approved by the exchange in mid-November, but the Securities and Exchange Commission still has to give its approval. So far, reaction is lukewarm.

The commission's new head, William Donaldson, favors replacing the exchange's self-regulatory apparatus with a totally separate, independent system. New York State Comptroller Alan Hevesi, who controls pension funds and is involved in a nationwide coalition aimed at reforming corporate governance, said he too was "disappointed"with the exchange's plan.

Still, the efforts are radical for an institution that has been resistant to change. "If the New York Stock Exchange gets reformed, which I think is a pretty good bet right now, this is on a par with the reforms of 1933 and 1934," Charles R. Geisst, a Wall Street historian and professor at Manhattan College in the Bronx, told The Washington Post recently.

And however the governance issue plays out, an even more sweeping change may soon alter the open auction system that has been central to the New York Stock Exchange's trading system for decades.

Like many self-styled reformers, Reed may find that his revolution overtakes him and acquires a life of its own. With the iron-willed Grasso gone, old discontents are bubbling to the surface, threatening to touch off a new battle over the structure of the exchange and the very shape of U.S. financial markets.

Lately, some of the exchange's biggest customers, among them giant mutual funds and government pension funds, are saying out loud what had only been whispered in the past: that it's time to dump the NYSE's "open outcry" trading system, which relies on middlemen called specialists, and move to an electronic system that would mean lower costs for investors and would offer fewer opportunities for corruption.

This would mean the end of the exchange's famous trading floor, with its frenzied auctions and piles of discarded order slips.

AN ENTERTAINING ANACHRONISM

In an age of microchips, the New York Stock Exchange trading floor is an entertaining anachronism.

At the exchange, when an order comes in, either by phone or electronically, it is sent to one of some 430 specialists, who handles all of the trading for that stock and several others. These specialists are the people in the colored jackets who can be seen striding around or waving bits of paper in TV news shots of the trading floor.

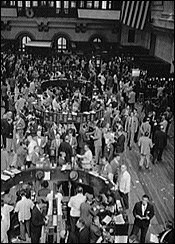

The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, 1955. The trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange, 1955. |

Each specialist, who is stationed at a booth on the floor of the exchange, essentially conducts an auction of his stocks, matching buyers and sellers or dipping into his own company's holdings to make sure there are enough shares available.

Once buyers and sellers are matched, the specialist reports the results of the transaction and the information is sent out to quote systems so that others know the stock's most recent trading price.

On electronic exchanges like Nasdaq, computers scan all the orders and match up buyers and sellers at the best available price.

The New York Stock Exchange's human-based trading system is, of course, supported by a vast network of electronics. Thanks to computers and productivity gains, it now trades an average of 1.5 billion shares a day; just a couple of decades ago it handled a couple of hundred million.

Critics say that computers are more efficient and far less likely to bend the rules for their own gain.

Because the New York Stock Exchange's specialists, unlike all other traders, have knowledge of all the bids and asking prices on a stock, they can gauge the direction of share prices before anybody else. Stock market officials say this allows them to maintain a fair and orderly market by stepping in and bringing sellers and buyers closer together. But critics charge that the specialists are perfectly positioned to fleece other traders.

"In the biggest, deepest market on the planet, I don't understand why there has to be someone who has advantage over everyone else" Scott DeSano, head of global equity trading at Fidelity, told USA Today. "All we're trying to promote are free, competitive markets."

Others point out that some of the large mutual funds that are criticizing the specialist system own stakes in fledgling electronic stock trading outfits that would like to siphon business away from the New York Stock Exchange.

The New York Stock Exchange is determined to defend its long-established ways.

"The specialist system works and it works very well," NYSE spokesman Rich Adamonis said.

WILL 'WALL STREET' STAY ON WALL STREET?

Amid all the uncertainty surrounding the stock exchange, one thing is clear:the New York Stock Exchange will stay in its columned 1901 edifice -- at least, for the moment.

A couple of years ago, it seemed virtually certain that the exchange would move to a new building across the street. In the biggest of all the Giuliani-era business retention deals, the city and the state agreed to shell out as much as $1.1 billion over a number of years to keep the New York Stock Exchange from carrying out its threat to leave for New Jersey. As part of the package, the city agreed to buy land for the exchange's new trading floor. A residential building on Wall Street was even emptied in anticipation of the project.

But the deal was put on hold after the September 11 attacks, and eventually the exchange, after rethinking the wisdom of building a conspicuous new headquarters, pulled out entirely. The city had already spent some $80 million.

So will Wall Street stay forever on Wall Street? The exchange now has an auxiliary facility in Brooklyn, at the Metrotech Center, in case of further disaster in Lower Manhattan, and another such facility at undisclosed location in the city. It is considering other sites in the suburbs.