New York City schools, argues Kozol, are in many ways unaffected by the Brown decision of 1954. |

Stuyvesant High School is one of the most vivid symbols of the consequences of decades of systematic racism in the United States. Black and Hispanic children make up about 72 percent of the citywide enrollment in the New York City public schools. At Stuyvesant – the most prestigious public school in the city – they make up less than six percent of enrollment.

In fact, the percentage of black kids who go to Stuyvesant has decreased dramatically in the last quarter century. Twenty-six years ago, black students represented almost 13 percent of the student body at Stuyvesant; today they represent 2.7 percent.

I'm not implying that the administration at Stuyvesant is made up of racists – they must be remarkable people to run such a wonderful school. Black and Latino students do not have access to Stuyvesant because they have not been adequately prepared to compete with the other students applying for a limited number of spots. What the racial gap in admissions represents is the devastating end result of the failure to educate black and Latino children effectively from the age of two and a half up to their 8th grade year.

It is impossible to improve the inferior quality of the education that minority children receive without confronting the fact that they are attending increasingly segregated schools; separate is still unequal. Yet that is exactly what New York policymakers are trying to do. Until it begins to follow the lead of several smaller cities across the country, New York's school system will continue to fail to serve the majority of its students.

THE RESEGREGATION OF AMERICAN SCHOOLS

|

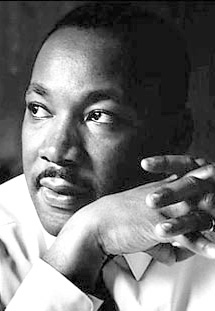

"We’ve got to come to see that the problem of racial injustice is a national problem. No community in this country can boast of clean hands in the area of brotherhood. Now in the North it’s different in that it doesn’t have the legal sanction that it has in the South. But it has its subtle and hidden forms and it exists in three areas: in the area of employment discrimination, in the area of housing discrimination, and in the area of de facto segregation in the public schools. And we must come to see that de facto segregation in the North is just as injurious as the actual segregation in the South. "

Martin Luther King, Speech at the Great March on Detroit in 1963.

Segregation has returned to public education with a vengeance, as a result of years of federal policies that started in the early 1990s when the US Supreme Court and the local federal courts began to rip apart the legacy of the Supreme Court's 1954 school desegration ruling, Brown v. Board of Education. The percentage of black children who now go to integrated schools has dropped to its lowest level since 1968.

New York State is the most segregated state for black and Latino children in America: seven out of eight black and Latino kids here go to segregated schools. The majority of them go to schools where no more than two to four percent of the children are white. Only Illinois, Michigan, and California come close to this abysmal record. The level of segregation statewide is due largely to New York City, which is probably the country's most segregated city

When it comes to residential integration and school integration, New York has an undeserved reputation for progressive values. For the last 40 years it has been one of the most regressive cities in America, in many ways unaffected by the Brown decision. The courts never tried to integrate New York, and the major media, including the New York Times, consistently opposed any drastic measures that would significantly integrate the city's system.

BLOOMBERG AND KLEIN'S EDUCATION REFORMS

The position of chancellor of New York City schools is an almost impossible job. I sometimes think that job was created so that one man or woman in New York could die for our sins every year. Like it or not, Chancellor Joel Klein's real job description is to mediate the separation of the races and put the best possible face on a flagrantly unequal system.

The Bloomberg administration's educational reforms have been centered on mayoral control of the schools. This probably gives the mayor and the chancellor better tools to approach the problems in the schools, and it is to their credit that they have used this power to get rid of the rote and drill, stimulus-response curriculum that was being used in failing schools across the city.

But we have wasted too much time in the last 20 years fiddling around with governance arrangements. The fact is that whether the school systems I visit are governed directly by the mayor independently, or through an appointed school board or an elected one, virtually all cities face the same calamity: a devastating gulf in the quality of education offered to minority kids as opposed to white kids.

NEW YORK CITY AND SMALL SCHOOLS

Alleged panaceas have been introduced repeatedly in every urban district since I first walked into a classroom in 1964. Every five years there's a "solution" to the problems of separate and unequal education -- a solution that never addresses the problems of either separate or unequal.

The newest magic pill that is being advertised is small schools, and it is one that Bloomberg and Klein have bought into.

Small schools are usually less chaotic than big schools; they are sometimes more intimate and relaxed than big schools. But the small school concept, which no one is proposing for the schools in white suburban districts, is essentially an anti-riot strategy for segregated children, an anti-turbulence measure, a short-term solution to perceived chaos in large segregated schools. Small, segregated, and unequal schools are only an incremental improvement over large, segregated and unequal schools. They don't address the basic issues.

In fact, in New York City small schools are being used, intentionally or not, in ways that widen the racial divide. On the one hand, we're seeing small schools that cater to very artistic, upscale Greenwich Village families. These schools are overwhelmingly attractive to white people. On the other hand, we're seeing a proliferation of so-called small academies for black and Latino students with names like Academy of Leadership, or the Academy of Business Enterprise. (In some other cities such schools are explicitly given names like the African American Academy). These schools tend to be even more segregated than larger ones.

At this point New York City, like many cities in America, is rolling out small schools as this year's trendy attempt to do an end run around inequality and segregation. It is not going to work on a significant basis. I predict that within ten years the entire small schools movement will collapse and be declared a failure.

REFORMS THAT ADDRESS THE REAL PROBLEM

Today, Bloomberg and Klein are trying their best to sweeten the pill of segregation rather than confronting it. But they have to confront it, and smaller cities have offered a model of how to do so.

The metropolitan New York City area is one of the most adamantly resistant sections of the nation, in which there has never been any serious attempt at voluntary integration programs between the city and the suburbs. This is in great contrast to St. Louis, Milwaukee, Boston, and several other cities, all of which have successful suburban integration programs for inner city children. While some of these programs were initially begun under court orders, others (Boston's, for example) are entirely voluntary and are supported by the parents of the suburbs because they believe that integrated schooling is of benefit to their own children.

In virtually all of the urban-suburban integration programs, the high school completion rate and graduation rate for black students average 90 to 95 percent or better, and the overwhelming number of these black kids go to college. There are waiting lists for all these programs; in St. Louis there are four applicants for every opening.

It is only about a fifteen minute ride from a typical, segregated Bronx neighborhood to one of the very first suburbs to the north of the Bronx – Bronxville, for example, one of the most affluent communities in the United States. It spends nearly $19,000 per pupil, compared to $11,600 in the Bronx. It has zero percent poverty in its public schools. Only one percent of its students are black or Latino. It would be a very short ride for almost any Bronx child to go to school in Bronxville or any of the other suburbs immediately to the north.

The chancellor and the mayor ought to be advocating for cross-district integration with the 40 or 50 affluent suburban districts that immediately surround New York City. Admittedly, this step would take extraordinary political audacity.

If he wanted to take a really visionary stance, Mayor Bloomberg could also turn small schools from institutions that reinforce segregation into places that help break it down. He could provide incentives for small schools to be created with the explicit goal of bringing the poorest children and the richest children, black, Latino, white and Asian children together in the same classrooms. If he were to take that step, and use the small school concept to achieve that goal, then he would have left behind a really decent legacy. He would have begun to make a serious dent in the intense racial isolation that continues to make New York the shame of the nation.

Jonathan Kozol is the author of seven books on urban education, and the winner of the National Book Award. His most recent book is "The Shame of the Nation: The Restoration of Apartheid Schooling in America."

Â