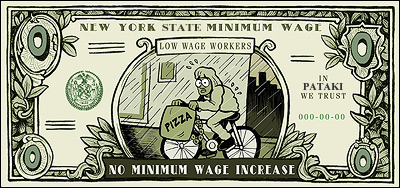

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

The issue of increasing New York State's minimum wage is again receiving considerable attention in the state capitol in Albany. And at first blush, a lot of New Yorkers stopped on the street would probably agree with the general idea of putting more money into the pockets of the working poor. Even small-business owners may well think that putting more money into the hands of their poorer customers is a good idea. But raising the minimum wage is not the same as delivering more income into the hands of people with low-skill jobs.

In fact, it is a complicated issue with many potentially serious implications for the future of our state as well as our lowest-skilled workers. So, when something like a hike in the minimum wage is proposed -- something that sounds simple, intuitive and benevolent -- responsible citizens should still take a step back and ask: Who really pays for the increase? The answers may surprise you.

In 1999, New York hiked the state minimum wage to $5.15 per hour and permanently tied it to the federal rate. This placed New York State on par with every other state that links its minimum wage to the federal wage and eliminated the problems caused when competing states have differing wage laws. It leveled the playing field and placed the issue of a minimum wage where it belongs -- with the federal government.

Nevertheless, organized labor is now pushing hard for a $1.60 -- or 31 percent -- increase in the state's minimum wage, notwithstanding the competitive disadvantages for business that would come from leapfrogging the federal rate.

A higher minimum wage puts strong upward pressure on the entire wage structure, which is the real reason that unions support it. But as any first-year economics major will tell you, if you tax something (in this case, jobs) or increase its cost, you end up with less demand for that thing. Can a state with one of the most expensive business climates in the nation, that has 300,000 unemployed and has lost 100 manufacturing jobs a day for the past five years, afford a new round of generalized wage inflation? The unions ought to think this through more thoroughly.

Perhaps most surprising, though, is big labor's indifference to the question of whether or not a hike in the minimum wage would really help the working poor and whether we can afford its wider social and economic impacts. Research from Michigan State University, for example, found that increases in the minimum wage encourage more teenagers to leave school and enter the workplace, displacing lower-skilled workers from their jobs.

Raising the minimum wage will work to deprive the working poor of job opportunities. Those most affected will be single parents, developmentally disabled persons, school dropouts and recent immigrants with poor language and reading skills. If you price entry-level labor higher than its real value, jobs will not be available for people whose skills are limited.

Then there is the impact on small businesses, considered by many to be the engine of growth and opportunity in the American economy. A small increase of $1.60 per hour would cost a bake shop with ten clerks and bakers over $30,000 per year, not counting the increases that a higher payroll brings in the costs of workers compensation insurance, unemployment insurance, Social Security taxes, Medicare taxes and even liability insurance in some cases. This is money that most small employers simply do not have. So, what will they do? Lay off workers, increase prices, or both.

When you consider that businesses with fewer than 100 employees create the majority of new jobs in New York, and that small business has created about two-thirds of the net new jobs in the United States since 1970, the proposal to hike the minimum begins to look less attractive.

Small businesses in New York are struggling against a tide of steadily rising costs. To reverse this trend and stimulate growth and jobs we must work to reduce the costs of doing business. Increasing the minimum wage at a time when we can least afford it just adds to the problem.

Now, is the sky going to fall if New York increased its minimum wage? Would we see dramatic layoffs and skyrocketing unemployment overnight? Probably not. But given that state spending, debt and taxes are already too high, the increase would hurt.

The final reason for opposing an increase is that it is not necessary. New York offers a wide array of generous programs, like the Earned Income Tax Credit, that provide cash assistance to encourage people to work without the negative impacts of a hike in the minimum wage. Other assistance comes from the Child and Dependent Care Credit, the federal Child Tax Credit, the Home Energy Assistance Program, and the Real Property Tax Circuit Breaker. Health benefits are provided through programs like Child Health Plus, Family Health Plus, Healthy NY and Medicaid. Nutritional assistance comes from Food Stamps, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (popularly known as WIC) program, and school breakfast and lunch programs. A college tuition tax credit also aids low-income families.

In 2003, the state and federal earned income tax credit was worth $5,465 per year for New York families making no more than twice the poverty level, providing over $700 million to the state's working families and individuals. With the tax credit counted, the effective hourly wage for a single parent with two children is $7.77 per hour (well above the wage rate sought by the Working Families Party). Add in the value of food stamps, free school meals and health insurance and the effective value of a minimum wage job tops $14 per hour.

New York today generously helps its most needy residents -- and in ways that do not damage small businesses or destroy job opportunities for teens and low-skilled people. Goodwill toward those who are less fortunate than us is natural -- but it should not cause us to turn off our minds and end up spreading far more ill than good.

Mark Alesse and Matthew Guilbault are with the New York chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group representing 20,000 small businesses in New York.

#####

Related Story

New York Workers Need A Raise

by Andrew Friedman and Fernando Ferrer