Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club held a conversation on June 22 at the Jefferson Market branch of the New York Public Library with Kenneth Ackerman,who has worked for both the executive and legislative branches of the federal government and is the author of several books, most recently "Boss Tweed: The Rise and Fall of the Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York." An edited transcript appears below:

Kenneth Ackerman(reading from his book): [William Magear] Tweed didn't invent civic corruption or ballot-box stuffing, but he and his Tammany crowd elevated the techniques to stunning proportions. They committed frauds gigantic on any scale, even if Tweed was personally guilty for only a small fraction of the whole. In later years, estimates of "Tweed Ring" total plunder jumped from the relatively modest $25 million to $45 million of the 1877 Aldermen's Committee to fully $200 million ($4 billion in modern dollars), a figure clearly inflated for dramatic impact but never scrutinized. It became part of the legend.

Tweed lived in a corrupt time, the Gilded Age, but he defined that era and pressed its boundaries. Even by his own day's standards, to call something "A Worse Fraud than Tweed's" spoke volumes. Tweed inherited a culture of graft endemic to New York City for generations and pushed it to its logical extreme, forcing the reformers to crack down.

After his excesses, no city in America could any longer tolerate wide-open graft or ballot-box abuse. Urban corruption didn't disappear, but it evolved and became more subtle. "A villain of more brains would have had a modest dwelling and would have guzzled in secret," E.L. Godkin wrote in the aftermath. George W. Plunkett, a Tammany leader of the next generation, well understood the point. "The politician who steals is worse than a thief," he'd say in 1905. "He is a fool."

TWEED IN PICTURES

So much of the Tweed story is visual. It is a story about the role of the media and the role of images, pictures, and cartoons. You can't really tell the story without the images. Tweed's persona was very much shaped by cartoonist Thomas Nast. Nast was a little too good at what he did. He was so clever and so vivid and wrote such funny compelling cartoon images that it was hard for Tweed, either in his lifetime or for posterity, to get away from the image Nast had created. I hope I've done a little bit to free Tweed from that stone around his neck.

Some of the pictures drawn of Tweed hit the nail on the head, and some don't.

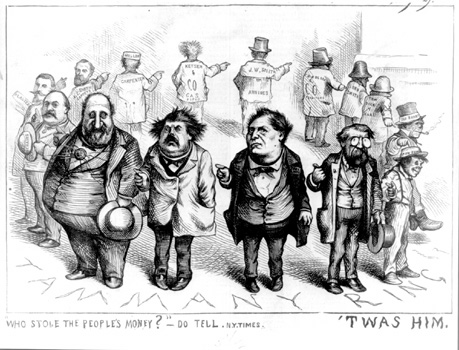

This is my personal favorite of the Nast cartoons, and it's one of the most famous of them. It was drawn just after the New York Times broke the story and they put out the so-called secret accounts, which showed the money the city paid for various contracts related to the Tweed courthouse. They were so big that it was impossible to believe the stories were true.

One example was the sum that was supposedly spent for chairs. It was enough to buy something like 315,000 chairs, so that if you lined them up in a row they would have made a line 17 miles long.

What the New York Times didn't show was who stole the money, or how the system worked. Even with the disclosures the Tweed ring could still feel that if they could keep silent they could still get away with it. Thomas Nast's cartoon, drawn right after that disclosure, shows this. Tweed himself is Nast's image of the American politician: big, fat, and arrogant with a silly look on his face, kind of ugly. Nast put looks on his characters' faces so that you'd always recognize them, kind of like Daffy Duck or Bugs Bunny. They're very distinctive pictures. The famous diamond that Tweed's friends gave him for a Christmas present was always on Tweed's chest in the cartoons. It was ten and a half karats, valued at $15,000 in 1870 money; that would be about $300,000 in modern money.

What you see is the Tammany ring, Tweed, Sweeney, Connelly, and the mayor Okie Hall all standing in a circle with the city contractors. Nash was notoriously bigoted and prejudiced towards the Irish and Catholics, and these characters are typical Irishmen for Nast: looking kind of like a gorilla, big square jaw, smoking a pipe, a whiskey bottle nearby, looking kind of nefarious. It's labeled: Tammany Ring. The caption says "Who stole the people's money, do tell." And everyone is pointing to the guy next to him and is saying 'Twas Him.'

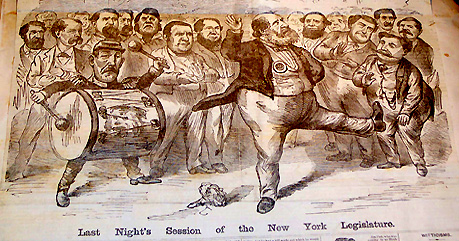

This was drawn by a friendlier artist. It shows a ball thrown by the Americus Club, which was Tweed's social club. Every year they rented out the New York Academy of Music on Union Square and threw a big party.

Here you see Tweed looking large but graceful, the center of attention, with people looking on in admiration. He's dancing a jig; he has a presence in the room. In real life he was about 300 lbs. Eating was the one major vice that he admitted to. He didn't smoke and he rarely drank, although when friends would come to visit he would always be ready with the cigars and whiskey bottles to give out favors.

Tweed was someone who, when he came into a room would work the crowd, make sure he got to know everyone. He would go up to you, shake your hand, tell you a story, share a joke, pat you on the back, and make sure by the time the night was over he knew your name, your family, what you did for a living. He would probably find some way to do you a favor, knowing that in this political world if he did a favor for you, you would do one back for him. He was the kind of person who if he promised to do something for you, you could have confidence he would do it; he had a very good reputation for, of all things, honesty.

That's the image of Tweed that I like in many ways more than Nast's, though they're both true. Part of the irony of Tweed is that it's wrong to be an apologist for him. You can't simply minimize what he did, and say 'everyone stole so it's not a big deal'. He stole much more than anyone else, but he had a big enough personality that the warm bloodedness of him, his effort to make right by the people around him, was just as prominent as the stealing. It may have been manipulative, it may have been pragmatic, but so what?

|

This cartoon is from 1875, also by Thomas Nast. It has a picture of an old brick building that served as the city jail. Tweed is shown as a giant too big to fit into the building. His head is sticking out one end and his feet the other. And the caption says "stone walls cannot imprison me, no prison is big enough to hold the boss, in on one side and out at the other."

Nast drew this drawing right at the time of Tweed's famous jailbreak. By 1875 Tweed recognized he was never getting out of jail, and he decided enough was enough. He paid about $60,000 in bribe money and arranged to sneak away. Ultimately, he made it as far as Cuba and then Spain before being re-arrested. He was on the run for about 10 months, mostly at sea. The Spanish authorities used Nast cartoons, including this one, to make the identification.

John Guzman: Is the implication that [President Ulysses S.] Grant had something to do with the escape and capture of Tweed correct?

Kenneth Ackerman: Definitely with the capture. The State Department got wind of where Tweed was when he landed on Cuba. At that time, early 1876, the presidential election had started. New York Governor Samuel Tilden was running against Rutherford Hayes, and there was a hope that if Tweed could somehow be captured and brought back to New York City he could be used as a weapon against Tilden.

So Grant arranged for Tweed to be captured and brought back on a very fast ship. Tweed managed to get wind of it and slip away in Cuba but Grant arranged for the Spanish to hand him over and send him back. The reason the attempt to use Tweed against Tilden fell through was that Tweed's trip back across the ocean was plagued by very, very bad weather and it took them twice as long as they expected.

As far as Grant or others being implicated in the escape itself, this gets into the realm of the very mysterious. There was clearly a helper, a man name Hunt, who joined Tweed in Florida and became his personal guide as they traveled through Cuba and then Spain. Who this Hunt was is one of the great mysteries of the whole story. When he was arrested in Spain along with Tweed they were originally both to be extradited to New York City. But at the last minute instructions came from Washington through the State Department to the American ministry in Spain saying "we want Tweed only, we don't want Hunt." So Hunt was let go. And it has always been a mystery who this person was.

TWEED'S LEGACY

Gotham Gazette: In the title of your book you say that Tweed "conceived the soul of modern New York." What do you mean by that?

Kenneth Ackerman: I was looking at personality. I saw in Tweed a person who was bold and smart and brassy. Whatever he did was the biggest, the most and the boldest, whether it was the way he went about fixing an election, or the house that he built on 5th Avenue, or the way he paved the streets, or the wedding he threw for his daughter.

In the State legislature, Tweed was one of 32 members when he joined it in the late 1860s; within a year he was the most important member. Not just because he was bribing other members, but because he was chairman of its two most important committees. He was the person who was involved in patronage, not just for New York City but for the canal system upstate. And that's where I come up with the "one who conceived the soul of modern New York." This is his city. This is the biggest city in America, and Tweed would be very comfortable with people who say that if it is not in New York it is not very important.

Gotham Gazette: So by "soul" you mean basically the bigness of it?

Kenneth Ackerman: The bigness, the personality, the energy, the confidence, to some extent the arrogance. It's part of our national persona as well, but New York had it first and demonstrates it the most.

Gotham Gazette: On the front page of the New York Times today, there is an article about Albany which lists, scandal by scandal, the corruption that's still going on. It mentions Guy Velella; it mentions an aide to the governor who gave a contract to a friend running a non-existent company; it mentions former US Senator Al D'Amato, who was paid $500,000 to make a simple phone call. Is there some of Tweed in that as well?

Kenneth Ackerman: There's some of Tweed in that. The political corruption lives at all levels today as it did then, although not in as outward form. There are more checks and balances today on corruption than there were in the 1860s and 1870s, probably because of Tweed. Today there are ethics committees in legislatures, and law enforcement is much more developed. The amount of record keeping that goes on for legislators' gifts, for instance, makes it much more difficult to be corrupt on that level. The cash accounting in the city government is worlds more advanced than it was in the 1870s. For someone to try to steal a billion dollars today from New York City, I'm not going to say it's impossible, but it would certainly not look like what Tweed did.

The places where you do have corruption on that level is in the corporate world.

What's similar is that the incentives are still there. Even though you don't have legislative bribery the way you did during the Tweed era in the state legislature, the amount of money that today goes to pay for members of Congress and United States senators and their campaigns is to some extent outrageous, even though it's legal.

Gotham Gazette: How about for mayor?

Kenneth Ackerman: It's still early in the mayor's race, so we'll see how that one goes. Mr. Bloomberg is bringing a lot of his own money to this.

What I do think is interesting is how much money city taxpayers pay for sports stadiums for teams that make tens of millions of dollars a year. We recently had a discussion about this in Washington D.C. where the city government is ending up paying $800 million for a new stadium for the Nationals baseball team. When they tried to fight it, Major League baseball threatened to pull the team out of town and the city caved. New York City had a lot more backbone on this than we did.

Gotham Gazette: But are the stadium issues Tweedian in some light?

Kenneth Ackerman: Well it is and it isn't. When I call something "Tweed-ish" to me it's not necessarily an insult. Something like the Jets stadium has Tweed written all over it. Tweed loved big projects that cost a lot of money, such as the Brooklyn Bridge or a large new building. He liked things that would employ hundreds or thousands of people, would send money to dozens of subcontractors and businesses, and would develop the economy in a part of the city.

Now certainly in Tweed's day there were cuts and padding all along the way, and jobs could be directed to your friends. Today there are union contracts and contracting rules that control that to some extent. So I don't think the dishonesty is there to anywhere near the extent in the Tweed Era. But the idea of big public works projects designed to keep people employed worked for Tweed and works today.

A lot of what Tweed built turned out in retrospect to be very useful. It was basically the infrastructure of the city, the sewer lines, the bridges, the parks, the sidewalks, things that have a lot of use. The question, which is a question of judgment, is whether a sports stadium 50 years from now is going to be considered useful.

Martha Soffer: Did Tweed have any influence on Robert Moses?

Kenneth Ackerman: There are some similarities to Robert Moses, caveat the corruption. But large-scale building was Tweed's signature, as it was later to become Moses' signature. Whether Tweed would have had the same attitude about breaking up neighborhoods is a whole other question. Part of the controversy with Robert Moses is that he felt so strongly about building highways that he was willing to run a path right through the middle of the South Bronx or right through the middle of Midtown Manhattan, regardless of the side effects that that would cause. Whether Tweed would have been more careful is a hypothetical question. We don't really know the answer. He obviously built a lot of big things but he was also someone with his ear to the ground in the neighborhoods, because he knew that was his base of support.

TWEED'S SYSTEM

Gotham Gazette: Your book deals mainly with Tweed's crimes. But Pete Hamill wrote in the New York Times that "One thing was certain: because of Tweed, New York got better, even for the poor." You seemed to be alluding to that. Do you agree with that, and what do you think were Tweed's main tangible accomplishments, aside from getting rich?

Kenneth Ackerman: Well, getting rich is an accomplishment. But I do agree with Hamill; part of the beauty and the irony of Tweed's system was that when it was working it did seem to work for everyone. The Tweed ring, when it ran city government, kept taxes low while spending lavishly on city improvements. Property values were up all over town.

It was a little like the era of the 1990s: the economy was very good and the stock market was on a roll. This was the period right after the Civil War, when railroads were having a boom, and telegraphs and even agriculture were having a good decade, and all of that money came into New York City. So there were a lot of factors causing the boom, but Tweed was encouraging it, he was riding it, and he was spending that money on the city while keeping taxes down.

As a result the city's wealthy class very much supported him. When he first got in trouble with the New York Times, he was able to get a group of city elders led by John Jacob Astor III, one of the wealthiest men in town, to go and look at the city books and publicly give them their blessing. At the same time Tweed did a lot of positive things for the poor, bringing immigrants into the political mainstream. Even though that may have been a cold-blooded pragmatic deal, it worked for the benefit of all. He was very loyal in terms of rewarding his friends, giving jobs to backers of his party.

When people, primarily Irish immigrants, would come out on election day and vote ten, twenty, thirty times that was not considered something to be embarrassed about. That was something many were proud of; it was your way of breaking in as a party worker. That would be a way for you to get a city job, to put bread on the table for your family, and to be part of the American mainstream. There are descriptions of these large demonstrations for Tweed either in Union Square or Tweed Plaza at what is at Canal St. and East Broadway. People would march behind placards saying "Tammany repeater."

But the picture is not complete unless you mention that there was a big crack in the middle of it. A lot of the money that was being spent, both for good and for bad, came from borrowing. It came from outsiders. Basically, Comptroller Richard Connolly financed the city by issuing dozens of kinds of stocks and bonds: park improvement bonds, courthouse improvement bonds, street improvement bonds, literally dozens of kinds that were being sold to Wall Street and to investors in Europe. In the three or four years that Tweed and his group were in control the city debt rose from about $30 million to close to $100 million. That was the crack in the system. It's a little bit like a cock-eyed Robin Hood. Tweed is like Robin Hood, if you assume that Robin Hood steals from the rich but keeps the first third for himself, gives the next third to the merry men, gives another cut of four or five percent to the local newspapers in Sherwood Forest to write good stories about what he does, encourages the poor to join the merry men so they can get a part of the take, and then gives the rest to the poor. Assume also that he doesn't steal from the rich in Sherwood Forest, but from the rich people two forests over. There you have Tweed.

Joan DeCamp: I'm interested in the stocks as a way to raise money. Today that would have to be done through public referendum, or by going through Albany. What was the political structure that would allow them to do this, and what eventually became of those bonds? I'm assuming that the robber barons and their friends knew better than to buy these.

Kenneth Ackerman: The way the city government structured itself was very different. Up through the late 1860s, Albany had gotten very involved in city government: it controlled the city legislature, it created a board of supervisors with 12 members (6 Democrats and 6 Republicans) which was supposed to make the city clean. Generally you could raise bonds almost by fiat if you could get the approval of the mayor and the comptroller.

The beauty of Tweed's system was that he managed to put allies at each of the key power points. In 1870 Tweed pushed through the legislature what was called the Tweed Charter, that solidified the structure and basically made Tweed, Sweeney, and Connelly un-removable. It gave them all revolving terms of 6 to 8 years, so their power could not be broken. For a while the board of alderman had power of the purse, but that was taken away during this period as well. Chamberlain Peter Sweeney actually controlled the bank accounts, and was the one who actually had access to the Treasury.

Under Tweed's system if you were a contactor who supplied anything from stationery to services to plastering to painting to construction to the city, you had to submit your bills to the board of supervisors. Basically Tweed had an arrangement with a few allies that when bills went through him you had to add 15 percent; that was the gratuity to the politicians for approving it. Over time they grew bolder: that number went up to 25, 35, 45, ultimately 65 percent at its height.

As far as what happened to all the bonds, some of them were considered a good investment for a while. But when the New York Times came out with its stories that provoked a crisis. The financial community was apoplectic and European bondholders suddenly cut off money. In August New York bonds stopped being traded on the Berlin Stock Exchange; that month there was also a bond offering in August on which the city received no bids. The Wall Street community realized that if the city defaulted not only would their own bond portfolios decrease in value but they would never get another penny from European investors.

The person who saved the day on the bonds was Andrew Green. Andrew Green was a very prominent reformer. He had been head of the Central Park committee and a leader of the New York Board of Education. When Tilden engineered his takeover of the comptroller's office - which was one of the key turning points of this whole affair - he figured out a way to get Connolly out. Connolly couldn't be fired, but if they could get him to appoint a deputy then the deputy couldn't be fired, either. Connelly went over to the reformers side, and they arranged for Green to become deputy in the dead of night during the weekend when no one was noticing.

It was a very, very gutsy thing for Green to take over. He came in with about 20 policemen and a squad of clerks and took over the comptroller's office. Nobody in city government would talk to him. There were threats that city police would come in with bayonets and kick him out, and he had to get his own police squad ready to fight for the office. Still, Green came in and stabilized the city government.

The first thing he did [was take] an inventory of how much actual cash was on hand, and he applied all of it to the city's next interest payment on its bonds. There was a period for about four or five weeks where there was no money to pay the salary of any city workers. Crowds of 40, 50, 60, 100, or 200 hungry, angry city workers - very tough people who had blood on their hands from recent riots - were threatening Andrew Green and others to pay their bills. This was the level that politics was on for a while. It took about two or three months to settle down. It took several years for Green and William Havemeyer, the next mayor who lasted only a short while as well, to restore the city's credit. The problem of these bonds hung over the city for years.

Martha Soffer: Did the police and the fire department became Irish under Tweed?

Kenneth Ackerman: The Irish immigrants were starting to become very engaged in politics during this period. The first high profile Irishmen in Tammany Hall actually came in the 1850s a little bit earlier. John Kelly, who would later become the Tammany boss, was a Congressman in the 1850s. There was a guy named Lynch who was the editor of the Leader, the Tammany newspaper, during the Civil War. Matthew Brennan is another who was prominent very early on. But during the Tweed Era the Irish were probably the biggest immigrant group that Tammany had that kind of close hold over. There was a very large German immigrant group in New York City as well, although German voters tended to be more independent politically. Some were Republicans, some were skeptical of Tweed, and in fact the German newspaper was one of the ones that questioned Tweed early on.

CHALLENGING THE TWEED LEGEND

Gotham Gazette: Was one of the misconceptions about Tweed that he was Irish? Is that one of the current misconceptions?

Kenneth Ackerman: He's not Irish. You do see every now and then a reference to him as being either Irish or Catholic because he was so tied to them. In fact when Nast and the New York Times were going after Tweed they tried to tie him to the Irish and the Catholics as a way of pummeling him publicly. But Tweed's family was Protestant. There was one time when he was checking in to the Blackwell's Island Penitentiary on Roosevelt Island in the East River, and Tweed was first asked "What's your occupation?" and he said "Statesman"; then he was asked "What's your religion?" and he said "None, my family is Protestant but for me none."

Gotham Gazette: That was already when he was in jail though. He might have said something different when he was still running for office.

Kenneth Ackerman: This was an era when people did actually try to distance themselves on religious issues. This wasn't an era where you wore your religion on your sleeve like you do today.

Gotham Gazette: You seem to speak of Tweed with a tone of sympathy. Did you like him so much when you started, or were there conceptions that you had of Tweed that changed throughout the time that you were writing this book?

Kenneth Ackerman: I guess my conception of Tweed did change while I was writing the book. My original conception of Tweed came from writing the book The Gold Ring, which I wrote in the late 1980s. It is about Jay Gould and Jim Fisk and their attempt to corner the gold market in 1869. In researching that story Tweed is always in the background, and I got the impression that during that period that nothing could happen in New York City without Tweed. When he got involved in something, it might be very crooked and corrupt and shady, but it always had a certain sense of organization. Tweed was someone who wouldn't steal something in a sloppy way. If he set about trying to manipulate an election he would do it in an organized, systematic way, throwing himself at it totally. He wouldn't do anything half-heartedly.

It is well known that Tweed stole between $40 million and $200 million, depending on the count. The thing that grabs your attention is that he wasn't an ignorant man or simply another corrupt politician.

When you write about someone like Boss Tweed you know at the outset that the man is crooked, that part isn't the surprising part. The thing that I really wasn't aware of was the extent to which the people who attacked Tweed stretched the rules to attack him. Most of the time he was being held in jail, he was being held on a pretext that would be laughed out of court today. The people attacking him had conflicting interests that were apparent to people at the time but get lost to us today. Samuel Tilden was really building a case for himself for the presidency. Then there was the man who brought Tweed down less directly, the county sheriff for New York City, Jimmy O'Brien. He managed to get his hands on the comptroller's office ledgers and give them to the New York Times; these are what became the secret accounts. O'Brien got his hands on these books primarily to try to blackmail Tweed for $350,000.

TWEED AND TAMMANY

Book Club Member: What does Tammany stand for?

Kenneth Ackerman: The Tammany Society goes back to the Revolutionary War. It started as a social club, named after an Indian chief, Chief Tamanend. It's not clear whether he was real or legendary, but he's noted for meeting William Penn when he landed in Pennsylvania, and there are also stories that he fought a great battle against an evil spirit that resulted in the creation of Niagara Falls. That's why there are Indian names all through the organization - the leaders are called "sachems" and the building is called the "wigwam."

Gotham Gazette: Your book is about the rise and fall of Tweed specifically, but Tammany Hall actually didn't fall with him. Can you go into what happened to Tammany afterwards? Why didn't it collapse if Tweed was the driving force behind the whole system?

Kenneth Ackerman: Tammany Hall as an institution remained active and effective for about 90 years after Tweed. After the Tweed fiasco, John Kelly became the next boss. His nickname was "Honest John." He was the sheriff, and he was generally an honest sheriff. When Mayor Havemeyer once accused him of corruption, Kelley actually brought a defamation lawsuit against him. (Havemeyer died in office before it could be litigated). Kelley was a very strong person and he rebuilt the machine, got it off the floor and got it working again and after that there were a number of very strong bosses.

Tammany had a very deep base built by Tweed's generation and the generation before him that could not be easily eliminated. The base among the immigrant communities, the network of local clubs and committees, stretched to literally every block in New York City.

The machine also provided services and people were loyal to it. In the early part of this century, one of the most prominent people it produced was Alfred Smith, who was eventually nominated for president of the United States. He had a progressive outlook, which came in part from the Tammany attitude of trying to deal with the real life problems of the people that it represented. Smith brought that into the legislative and political arenas in a way that no one else had up until that time. It later became the foundation for the New Deal.

Tammany remained strong until the 1930s, and at that point Fiorello LaGuardia was elected mayor. LaGuardia was a combination Republican-Fusionist-Liberal - he had several lines on the ballot, but the Democratic line was not one of them. As a result for a period of about a dozen years Tammany was cut off from patronage. And that was when they lost the nice building on Union Square and they moved into an office suite in an office building. Around that time Tammany and the Democratic party split.

Tammany Hall had a resurgence in the 1950s under the boss a man name Carmine De Sapio who became prominent behind a number of leading politicians. He was knocked down by a group of reformers in the early 1960s. There were corruption charges and he spent a couple of years in jail. The nice tie-in to modern times is that De Sapio's final defeat came in a local election in this neighborhood where we're sitting right now, Greenwich Village. It was over a local leadership position, and he was defeated by a man named Edward Koch. Koch later went on to become mayor.

Â