Try to fit the Gerrymandered districts together: Play Gotham Gazette's Poli-Tetris. Related: |

Two Brooklynites go to sleep at the same time in the same Assembly district. The next morning, one wakes up in the 52nd, the other in the 57th. Neither left his bed. What happened?

This is not a physics problem, it is a political one – or rather, it was a political solution to a political problem posed by a candidate who ran for the New York State Assembly.

Hakeem Jeffries ran for the Assembly against incumbent Roger Green in the 2000 election, and won more than 40 percent of the vote— too close for comfort in the world of New York electoral politics. Two years later, when the state had to draw up new district lines, Jeffries discovered that he no longer lived in the same district as Green. His home was on a block that had been "redrawn" into a different Assembly district.

The state legislature – Green’s colleagues – are in charge of drawing district lines, and the guidelines for doing so have presented little if any obstacle to this type of political maneuvering, most commonly known as gerrymandering.

“It’s just not right,” said Assemblymember Sandy Galef (Westchester/Putnam). “We need to get this process out of the hands of legislators.” Galef has sponsored legislation nearly every year since 1998 that would set up an independent redistricting commission through a constitutional amendment – just one of several proposals throughout the country, as well as throughout the state, that aim finally to clean up the suspect process. It will not be easy.

As It Stands

The constitutions of both the United States and of New York State require the state to redraw state legislative and Congressional district every 10 years, in order to keep the district of roughly equal population size. This is intended to ensure that each citizen's vote is of equal weight. But the guidelines for this redistricting are vague at best.

For certain, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 requires protection for specific minority voting blocs to ensure that their vote is not diluted. However, this does not extend to all groups and the requirements to gain even this protection are problematic.

In New York State redistricting is officially done by the six members of the Legislative Task Force on Demographic Research and Reapportionment (LATFOR), who are appointed by legislative leaders on both sides of the aisle. The task force thus takes on the aura of a disinterested bipartisan body. In reality, the leaders of each house have agreed to split the spoils. Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver controls redistricting for the Assembly and Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno controls redistricting for the Senate. And if that power divide isn't distressing enough, state law and legal precedent have established that district lines CAN be drawn in order to ensure that party representation and incumbency are protected.

Incumbency Protection

In Texas, redistricting was used by the Republicans in two successive congressional elections to knock Democrats out of office. But New York legislative leaders are more subtle, content to protect all incumbents. That is why, for three decades, the Republicans have safely controlled the state Senate and the Democrats have controlled the state Assembly.

In Roger Green's case, the newly drawn lines placed a major obstacle in challenger Hakeem Jeffries' path to office — he would have had to move to serve the district he formerly lived in.

Also in 2000, challenger Susan Lasher mounted a nearly-successful effort at unseating incumbent Adele Cohen in the Democratic primary for the New York State Assembly. Cohen won the election, but by a mere 100 votes.

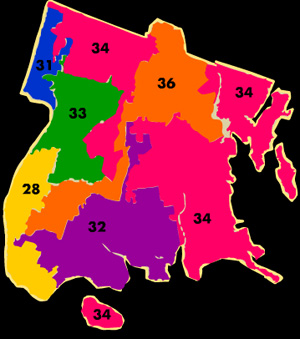

Lasher's strong showing at the polls was based largely on her support from the growing Russian-American constituency in the Coney Island/Brighton Beach section of the district; she garnered over 75 percent of the votes there. When district maps were redrawn after that election, portions of Brighton Beach had been removed from the district, while greater portions of Bay Ridge were added, an area where Cohen garnered a large percentage of her votes (2002 Map - 1992 Map). "They cut the lines to cut the [Russian-American] community up into pieces," Lasher said.

The system of legislative control of the redistricting process that marginalized Hakeem Jeffries and alienated Susan Lasher, has profound consequences for every New Yorker. It has created a government that is now commonly called the most dysfunctional in the nation. The troika of Albany leadership -- Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver, Senate Majority Leader Joe Bruno and Governor George Pataki, who have dominated New York State politics for nearly a decade -- has overseen a government that routinely fails to pass a budget on time, has seen reform of the Rockefeller Drug Laws wither for 10 years despite widespread support, and has done nothing in the face of a court order to overhaul education funding to provide schoolchildren with the sound, basic education that they deserve. No discussion of the troika's dysfunction would be complete without mention of the 800-pound gorilla, Medicaid, and the utter inability to develop a plan to implement the federally mandated Help America Vote Act (HAVA).

The politicians and political pundits would like you to believe that things are getting better. They dubbed 2004 a bad year for incumbents. But only seven incumbents running for re-election were not elected for another two-year term.

In fact, overall, New York State ranks near the bottom in terms of turnover in its legislative races. In 2002 no incumbent lost a general-election race in New York. Over the past twenty years, only 30 incumbents have lost general election races. This is an incumbency return rate statewide that hovers around 98 percent.

However, the push for redistricting reform is gaining ground. It happened in Montana in 1972, in Arizona in 2000, and in Iowa in 2001. No fewer than eight states are currently pushing to make redistricting a truly non-partisan process. More and more of the public seems to be responding to what is clearly widespread abuse.

California and New York Moving Ahead?

Out in California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger has his sights set on accomplishing legislative redistricting reform by hook or by crook. He has sounded the call and has let the legislature know that if they don't act to appoint an independent commission to draw district lines he will take the issue directly to the voters.

While cynics point out that his short-term goals may be set on breaking up the power monopoly held by the Democrats in Sacramento (the House is 48-32 Democrat to Republican and the Senate is 25-15 Democrat to Republican), the long term benefits and the impetus this will provide to reform movements around the country could be monumental. Wrestling power and high-tech redistricting tools away from well-financed and entrenched California incumbents could prove harder than defeating Dolph Lundgren in Rocky IV (or was it Sly Stallone who did that?).

What California has that New York doesn't is a well-oiled citizen initiative process that the Governator can flex if his muscle isn't powerful enough in Sacramento.

Here in New York we have Assemblymember Michael Gianaris (Queens), a likely candidate for Attorney General, who is looking to stamp his name on the history book of reform in the state, and a growing outcry of fed-up citizens. Gianaris is working on legislation that will be introduced in the near future that would accomplish legislative and congressional redistricting through the legislative process. He will soon have the task of not only convincing enough Assembly Democrats, but the Republican-led Senate as well, that this is in the public's best interest.

Gianaris' legislation would alter the commission's composition to give the minority party more leverage, yet would not give the power to an entity entirely independent of the legislature. He says that would signal the death of the bill.

"Allowing the minority party the opportunity to participate in the process will ensure a more balanced approach to redistricting," states Gianaris, "and it is likely that plans approved by both sides of the aisle will result in a more inclusive government that distributes power more equitably."

In addition to the creation of a new redistricting commission, Gianaris' bill would create a host of new and important guidelines, including a requirement that would prevent the commission from drawing lines to favor or oppose any political party, or any incumbent federal or state legislator. While it will still be up to the commission to interpret these guidelines as they see fit, ultimately, the courts may have the last say, and having this clause included could be just the tonic the state needs to create a more responsive and accountable legislature.