Seward Park High School

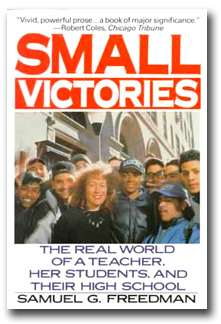

Gotham Gazette's Reading NYC Book Club met with author Samuel Freedman, New York Times education columnist, and Jessica Siegel, the teacher who is one of the subjectsof “Small Victories: The Real World of a Teacher, Her Students and Their High School."An edited transcript is below:

Gotham Gazette: “Small Victories” is about a high school on the lower East Side during the 1987-88 school year. Mr. Freedman, this book was written almost 20 years ago. Is it a picture of a certain time in New York City history, or do students still face these same issues in 2006.

Samuel Freedman: It is close to 20 years, but I think that a lot of the issues remain very familiar in the sense that you’re still dealing with a public school system that doesn’t have enough resources, that doesn’t have enough modern enough facilities, that’s contending with a very economically poor student body, that’s contending with the biggest wave of immigration coming into the city in more than a century.

Some aspects have changed. At the time I was writing this book, the school system was divided between grades kindergarten through 8 -- which were decentralized and overseen by elected community boards, which tended to be real sinkholes of corruption -- and then the high schools, which were centralized and actually, I felt, run pretty effectively through borough offices and then, ultimately, the Board of Ed.

Another thing that’s different is that, much to my chagrin, schools, like Seward, have become a ready symbol, and I think, not a correct one, under the current leadership of the Department of Ed, for everything that’s seen as ailing in secondary ed. That’s a perception I don’t particularly share.

The superhuman efforts by a number of the teachers and the tremendous will on the part of many of the students to get to college, to have fruitful lives, to really become citizens in every sense of the word -- that’s unchanged and that’s still the very best part of what goes on in New York City public schools. It’s sort of the everyday miracle.

Gotham Gazette: Ms. Siegel, the school you teach at now, Abraham Lincoln High School, in some ways seems similar to Seward Park. It’s a large high school, and there are 30 different languages spoken there, according to Inside Schools. How is the experience you’re having now similar to the one you had in 1987-’88, and how is it different?

Jessica Siegel: Well, the stuff you just talked about is very similar. A lot of immigrants. In the case of Abraham Lincoln, Russians, East Indians, Latinos, and then, of course, native-born African Americans who are an important part of the school. And at Seward Park, it was predominantly Latino, Chinese, Asian, some whites, believe it or not, and African American.

"With all that school had going for it, there should have been a way to keep it open rather than to break it apart."

What’s changed is the school system, and the centralization of the school system, where schools like Abraham Lincoln and Seward Park are now targets for reorganization and are seen, as Sam said, as failures. So there’s this centralized sense about curriculum. Abraham Lincoln has been on the impact list, which means that the amount of incidents in the school is too high, so they’re constantly being monitored by the superintendent.

It’s really under the microscope. And so people are running scared. Teachers are running scared because the pressure is on from the top down to the teachers in a way that I think has a negative aspect on teaching and learning.

Gotham Gazette: One of the things that struck me about your teaching experience at Seward Park was the journalism class. It seemed like you had a lot of freedom to work with individual students. Would having a class like that be more difficult in this system?

Jessica Siegel: Well, I’m teaching journalism this term. I started a journalism class. One of the reasons that I went to Abraham Lincoln was I liked the principal, and he wanted to get a journalism class up and running.

Interestingly enough Abraham Lincoln – like Seward Park – has alumni who feel really strongly about this school. For some of the older alumni, the school newspaper had a really big effect on them, and supposedly they wanted the newspaper up and running. So I'm in the process of trying to get the first issue out. It's a way to have kids write about what they care about.

The problem is, going back to the point that Sam made about big schools versus small schools is that a lot of classes like journalism electives are eliminated in small schools. Some of the classes that manage to pull kids in – music class or art class – are eliminated. It's one of the unintended consequences of this big push for small schools that a lot of the classes that turn kids on to school are eliminated.

The Push for Small Schools

Gotham Gazette: Do either of you see an advantage to small schools? Is it a tradeoff or just a misguided policy?

Samuel Freedman: I think it is a tradeoff, and I'm not a doctrinaire foe of small schools by any means. One of the best arguments in their favor is that in larger schools there is a greater chance kids are going to get lost in the massiveness of 2,500 to 4,000 students. They are much less likely to get lost in a school of 300 or 400.

I am really concerned, though, in a couple of ways. This was something that started under former Schools Chancellor Joe Fernandez – it predates Joel Klein by a decade or more. There was an earlier generation of small schools that were created with a lot more deliberation, they were opened a lot more gradually, they had a much more thought-through pedagogical center or core academic area. It's not surprising that they have been successful.

The problem is that you have this tail of this big grant from the Gates Foundation wagging this policy dog at the Department of Ed. Because Gates has a big priority to start small schools, the Department of Education is jumpstarting 50 a year, year after year. It's just impossible to have quality opening up schools in that kind of frenetic way. It also means a lot of these schools get opened up with these ultra-niche academic orientations – sports careers or architecture – that I think are really preposterous for a ninth grader. I think what they tend to do is serve the interests of community organizations that are sponsors. These may be perfectly well-intended sponsoring groups, but that doesn't mean that the high school as a whole is going to work with a curriculum that is defined that narrowly, especially when there is a good reason to put more emphasis on language, science, math and a lot of the core subjects.

Two more points: One, it has created an even more Manichean system of who gets the best students and who gets the rest of the students. I saw that already when I wrote the book about Seward. Seward's incoming freshman, 10 percent of them were reading at grade level. Amazingly Seward graduated 30 percent reading at grade level, which I saw as a huge accomplishment. Now that there are extra layers of skimming going on, by the time kids get into the old-fashioned zoned high schools there is a sense that this is the school of last resort – anyone with any real prospects has gotten in somewhere else. Plus as schools get shut down to be broken down into smaller schools – Martin Luther King in Manhattan is a good example -- the unwanted kids get shunted into other zoned high schools. The detritus of King gets sent to Washington Irving or Norman Thomas and overcrowds those schools, destabilizes those schools, and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy in which schools that were functioning at a satisfactory level if not an exalted one suddenly are struggling not to have fights every day.

Two more points: One, it has created an even more Manichean system of who gets the best students and who gets the rest of the students. I saw that already when I wrote the book about Seward. Seward's incoming freshman, 10 percent of them were reading at grade level. Amazingly Seward graduated 30 percent reading at grade level, which I saw as a huge accomplishment. Now that there are extra layers of skimming going on, by the time kids get into the old-fashioned zoned high schools there is a sense that this is the school of last resort – anyone with any real prospects has gotten in somewhere else. Plus as schools get shut down to be broken down into smaller schools – Martin Luther King in Manhattan is a good example -- the unwanted kids get shunted into other zoned high schools. The detritus of King gets sent to Washington Irving or Norman Thomas and overcrowds those schools, destabilizes those schools, and creates a self-fulfilling prophecy in which schools that were functioning at a satisfactory level if not an exalted one suddenly are struggling not to have fights every day.

The last thing is that the critical mass of large schools allows for sports teams, school newspapers, musical groups, debate clubs, all kinds of extra-curricular activities. While it is true, large schools can't give the individual attention small school can in terms of guidance counselors or classes, having a school newspaper is a way of giving individual attention that small schools cannot offer.

Jessica Siegel: Let me jump off on that. A lot of the big schools in Brooklyn have become extremely overcrowded. The kids who don't get into these small schools end up in these large schools, and the hallways become extremely crowded. If there aren't difficulties in the school already this helps to create them.

I feel strongly about the intimacy small schools can give. But the key is small class sizes. With the exception of the Campaign for Fiscal Equity, few people are talking about small class sizes, which could be in a small school or a large school. I don't want to be idealistic, but if you have a class of 20 you can do anything. Great teachers can be greater, and even mediocre teachers can be a lot better, because you have fewer students. Speaking as an English teacher, you'd have fewer papers to mark, so you can give more essays or other kinds of writing than if you have 34 kids in a class. It's obvious, but nobody is talking about it. The whole discussion is small schools, small schools, small schools, but it's small class sizes.

I also think that if they had really thought through these small schools, they could have the extra curricular activities – journalism, band, chorus – in the building that houses four or five schools. Seward Park is now five schools. Why not have them join together in putting together a school newspaper or having a band? It's about this competition for getting better students rather than working together and having those kinds of activities.

Does Integration Matter?

Gotham Gazette: Jonathan Kozol recently wrote an article for Gotham Gazette Segregated Schools: Shame Of The City, in which he argued that one issue that is being ignored is racial segregation. He said that until that is confronted, other reforms will not accomplish much. What is your perspective on that?

Jessica Siegel: What is the percentage of the public schools students that are children or color? Eighty-five percent? It's not even relevant. That's who is in the public schools. To me it's not an issue of segregation so much as what kind of education you are going to give to the kids there.

Samuel Freedman: I completely agree with Jessica. Kozol espouses a point of view you pick up in education schools. But it is a high-minded excuse for paralysis. It would be great to rewind the clock back to 1973 when the case out of metropolitan Detroit was decided and the Supreme Court decided there could not be regional remedies [to school segregation]. When that ruling came down, it was basically the end of what Kozol would wish for. Would it have been better if that ruling went the other way? Yes, but that was 32 years ago. It's part of educational suicide to say now, however well intentioned you are, that until you solve poverty or segregation nothing can happen in the schools. Something has to be able to happen in the schools.

One of the things I saw at Seward was that demographically and economically, you would say nothing should have happened there. But amazing things actually did happen there. Would it have been better if half of that school were kids of upper middle class parents from the East Village? Probably, but in the meantime you had to teach and make things happen for the kids who are there. So by saying nothing can ever change until poverty and racism are solved is like saying you can never have any effect -- which is the worst message.

The No Child Left Behind law requires disaggregation of data by race. No matter what No Child Left Behind's faults are -- and there are many -- this has been an important way to bring the equity issue to bear.

There is a real feeling in a lot of the minority community that, whether or not integration ever would have been the remedy, it's not the remedy now. Something has got to happen for our children right now. I know someone like Kozol sees himself as speaking on behalf of these families and students, but I think right now he speaks against their interests in a way.

The Closing of Seward Park

Gotham Gazette: Can you speak a little bit about what has happened in Seward Park since the book? Both of you alluded to the fact that it has been broken up into small schools.

Samuel Freedman: I think it’s criminal that a school like Seward should have to be closed, and I think it’s an indictment of the Department of Education and its policies. With all that school had going for it, there should have been a way to keep it open rather than to break it apart. It should never have come to this.

Seward had a great faculty when I was doing the book, and a lot of those people are still teaching at various schools, a superb faculty. But it also had a really, really phenomenal principal, a guy name Noel Kriftcher and I think if I had to point to one thing, aside from this misguided Department of Education policy, that damaged Seward and made it vulnerable to this policy is that there was a definite decline in the quality of the principals over the years at Seward. Noel Kriftcher was a uniquely talented guy who was bright, experienced and savvy dealing with the board and had high standards. He also was a physical presence and an athlete, someone who could do well in an urban school and keep order without metal detectors. The guy who replaced him, who was his protégé, was a capable guy who also kept the school in pretty decent shape and then I think it tailed off.

What this points to is that even with a really good faculty and even in some ways some very good student demographics you need to have a great principal, and you need to cultivate people like that.

One of the other problems the Department of Education has had is that they have not adequately nurtured the talent within the system to create and bring along the next generation of great principals. They took a real bold and I think mistaken step -- again with a lot of private philanthropic money – to create a principals academy aimed at taking people either from other cities with some educational experience or taking people with no educational experience and thinking that you could in short order turn them into quality New York City principals. And that was folly. In the course of doing that program, they jettisoned, out of their arrogance, an existing program for a fraction of the money that used experienced New York City principals to mentor young future principals and assistant principals and that had been really successful.

Where Are They Now?

Gotham Gazette: Are you still in contact with the people in the book.

Jessica Siegel: Oh yeah. Noel Kriftcher I see every so often. He's now at Polytechnic University doing collaborative work with high schools.

The thing about this book that is truly remarkable -- and I can talk about it almost as if I'm not a character in it -- is that there are very few books in which minority teenagers come across as complicated individuals. They seem equal to me... It's not written as this missionary coming in, this wonderful, perfect person. It's very much about me, one teacher, and other teachers, and the students as equals, in terms being of interesting, complex individuals.

Angel Fuster was one of my students. I am in touch with him – in fact I spoke with him about two days ago. He is a lawyer. Carlos Pimentel also is a lawyer.

Denise Simone, who was another one of the teachers there, is in one of those principal institutes. She is going to be a principal. She has been teaching for 25 years, and is one of the few people who has been an experienced teacher; she is with people who have been teaching for two years or four years.

Bruce Baskind, another colleague of mine, is a social studies teacher at Brooklyn Tech.

Steve Anderson was at Seward Park until its very end and is now going to help design one of those small schools.

A Teacher’s Trials

Gotham Gazette: Throughout the book, there is a tension between you loving teaching and you wanting to leave. At the end of the book -– and I'm sorry if anyone hasn’t gotten to the end –- you do leave. But then you come back to the New York City school system. Can you talk a bit about why you wanted to stay so much and why you wanted to leave.

Jessica Siegel: Well, it's a hard job. In high school, you teach five classes a day, and if you have 35 kids in a class, and I'm going back to that issue of class size, and you're an English teacher and you feel strongly about writing, you're always assigning papers. So it's hard.

But it's also one of the most rewarding careers you can possibly have. You know you're doing something worthwhile. And at least with adolescents, there is this interesting combination of maturity and immaturity. You get immediate feedback about how you're doing. That can be both good and bad, but ultimately it’s rewarding.

"If you have a class of 20 you can do anything. Great teachers can be greater, and even mediocre teachers can be a lot better."

At Brooklyn College I've taught a lot of the teaching fellows. My feeling about that program is that it's throwing people in with very little preparation. While some of the people are staying -– and there are some very remarkable people -– I wonder what the dropout rate is after two years. Probably a different version of the Teacher Corps –- a program started in the 1960s where people came in for a year and got to know the community and slowly came into [teaching] -– might work better than throwing people in with only a summer's worth of preparation. Because it's very difficult.

There needs to be more thought about how you can both bring people in and get them to stay. Not making them sign on the dotted line that they have to stay for five years, but what can you do to make it easier for people to adapt. Another thing in the high school might be having them teach only three or four classes for a couple of years while they get acclimated.

Joan DeCamp: A lot of people would like to go into teaching but when I look at it the experience is so unsupportive compared to any other job. If you go to a company or a business, they don’t just sit you down at a desk and say, “OK, here’s your job. We’ll see you at the end of the year and see if you got it done.”

It seems teachers are not supported. It’s not a team environment, or a collegial environment because you have to be in the class all the time with students. I don’t get the sense that it’s your own classroom, your own privacy, your own place. There’s no phone access. There’s not a whole lot of things that most professionals have and would want to have. And I think that keeps a lot of people from going into it.

Samuel Freedman: The kinds of things you talked about –- not having your own room, not having access to a phone -– these are some things that push really good teachers out of New York to either private schools or to suburban schools. And it goes right to issues of money. The Campaign for Fiscal Equity suit supposedly got settled, and that money still has not been dispersed. And when it comes through the question will be how will it be spent. It seems to me you articulated some of these poignantly basic, fundamental things that would help teachers feel a higher regard and more comfortable continuing on the job.

Helping Students with Problems

Kate Stoehr: I work in the foster care system, and I’m thinking about behaviors and mental health issues, stuff that is going on at home and how that bleeds into the classroom. I don’t know how you would even begin to teach a classroom of 35 kids of whom 30 or whatever might have extraordinarily high mental health needs and really messy family situations. I only know about it from the foster care perspective. What from a teacher’s perspective can we do?

Jessica Siegel: Well, like I said, smaller class sizes. Obviously they need to have social workers and guidance counselors and make guidance counselors put more emphasis on counseling as opposed to just helping the kids with their programs. Bringing in community based organizations so there’s the connection to the community, all those kinds of things.

But I think again it’s really about making it so that teachers are working with a smaller number of students. The whole point is getting to know your students well. If you have 35 times 5 – 175 kids – how can you really get to know all of them well? Strangely enough you may get to know the kids who give you the most difficulty but all these other kids get lost in the shuffle.

Samuel Freedman: One really interesting program which I’ve written about is a pilot program out in Oakland, California, that put mental health clinics into high schools, with foundation funding. The idea was to address exactly what you’re talking about, Kate. In Oakland, there was a tremendous problem with gang violence and drive-by shootings, really post-traumatic stress disorder, if you had to put a name on it, for kids in their teens who had experienced or witnessed horrific violence. They tried to bring the mental health service right there. Ideally you do that in many other places.

It’s a shame we tend to think of school health clinics only to dispense the TB test and the flu shot or, in a more volatile setting, condoms issue, when they could do a lot of mental health work as well.

But I want to say a few things I saw at Seward Park that were important, short of being able to bring in that kind of mental health service. I was always struck that Jessica and the other teachers, even with the huge numbers of students in the school, shared so much information with one another. When teachers had lunch with one another, when they sat in the English or the history office together, the friendships they had with the guidance counselors, with truant officers, with the coaches, with the principal, was really a kind of informal loop of information. It was good for the teachers because they felt less isolated but it was also a sharing of information.

But I want to say a few things I saw at Seward Park that were important, short of being able to bring in that kind of mental health service. I was always struck that Jessica and the other teachers, even with the huge numbers of students in the school, shared so much information with one another. When teachers had lunch with one another, when they sat in the English or the history office together, the friendships they had with the guidance counselors, with truant officers, with the coaches, with the principal, was really a kind of informal loop of information. It was good for the teachers because they felt less isolated but it was also a sharing of information.

The other thing, and it’s part of what’s magical about education and part of why I’ve never tired of writing about it, is that good teaching or great teaching gives kids a way to express and deal with traumas. There are layers and layers and layers of domestic disturbance and violence and God knows what else. The kids I knew at Seward: One kid whose parents had moved back to the Dominican Republic, 17 years old, living on his own. Another girl who moved out from an abusive home and was in a shelter basically. Kids who had to work jobs, parents who were well-meaning but didn’t know English or who were working multiple jobs and were never around. Violence. Kids running gauntlets of drug dealers on the way to school.

One thing Jessica did that was very successful for teaching but also for these kids’ mental health was to make a lot of use out of writing autobiographically. It was not the only writing they did, but it gave them a place to put those feelings and try to make sense of it and also let Jessica know what the kids were dealing with and find a way to respond.

That was one level, and the school newspaper was another. In the book, I write about a boy who was gay, and I don’t know if he was out or not, but having him write about the experience of gay teenagers was a way of trying to make sense of his own experience. The school newspaper allowed that. There was also a very good creative writing teacher, who did a lot of autobiographical fiction and poetry with the kids.

And then finally there’s something about works of great literature that allowed kids to make the imaginative leap from their experience on the Lower East Side in 1987 to other places. I’ll never forget Jessica teaching “The Great Gatsby” to this class of new immigrants. Because of that book, and her ability and their brains, these kids were able to make the connection between their aspirations, their desire to reinvent themselves, to pretend to be things they weren’t and pass over into elite white society to Gatsby. And they were also able to see through that book what terrible things can be lost in the process.

That’s a book that certain people would say shouldn’t be taught in an overwhelmingly minority school. It’s a dead white European male book. And yet it isn’t. It’s a book about human nature and the kids saw themselves in it, and that was another way to make sense of it.

One of the first things Jessica said to me was how amazed she was at what her kids could deal with and still function, still go to school and do work and get to college. Some of what was valuable was that school was kind of a refuge for them, school was the most unchaotic place.

One of my students at Columbia Journalism School is finishing a book about an inner city Catholic high school – Rice High School in Harlem – and the title of the book is “The Street Stops Here,” which was a motto of the late principal there, Orlando Gober. It was an idea not just of crime, but a more general sense of chaos and confusion and family tragedy. School was the safe place, the one orderly part of their lives, and that allowed them to do amazing things.

The Joel Klein Regime

Gotham Gazette: You both talked about small schools, and it seems to some people looking at what's going on in education in the city that the mayor and the chancellor are not doing anything to change high schools beyond breaking them up. Is that a fair perception? What else would you would like to see them do to bring down the dropout rate down and make kids more connected with high schools?

Jessica Siegel: I think there are a number of different systems now. They aren’t looking so closely at the newer schools but they are putting a lot of pressure on the big schools. I’m not necessarily against centralization or mayoral control but I think the chancellor has come in with an attitude that “I’m going to clean up the schools” and there hasn’t been enough credence given to the professionals who are working there. I’ve run into any number of people that have left -- people with as much experience as me or more -- who have felt that they haven’t been respected and that the chancellor and the people that he’s hired have the assumption that “we know the answers.”

There’s hasn’t been enough of let’s stop and see what’s going right and what can we build on. Education journalists like Sam have talked about all the MBAs that have been hired by the chancellor with the assumption that somebody who knows about education will be part of the system and they can’t be trusted. I think that’s a bad attitude. I think that education is a very complex field that involves human beings, it involves a multiplicity of experiences and issues

There’s a tremendous amount of expertise that just hasn’t been utilized. Instead there’s been bulldozing over: “We have the right answer, just follow what we say,” and that kind of thing. It’s disturbing and it’s not respectful of teachers as a profession.

Samuel Freedman: There was a view by Klein and his regime at the Department of Education that everything that preceded them was no good because it preceded them. I don’t think the people have ill intent. It’s bad policy and damaging moves by people who mean to do well but don’t know better.

One of the reasons they don’t know better is they have made a point not to tap the incredible expertise and talent that was in the New York school system before they got here. New York City is the envy of every other big city school system in the country. It’s the envy for its academic result, it’s the envy for the percentage of the middle and upper middle class of all races it’s kept in the system, it’s the envy for the quality of teachers and administrators it has, a lot of which has to do with the historical commitment to public education, in this city. You have to know how to root out some of the terrible parts, like the community school boards, but also look for the brilliant people who are in the system and keep them. And by all means don’t drive them into early retirement, which is exactly what’s been happening. So much expertise, so much wisdom has been lost.

Also in this desire to reinvent the wheels and to pretend that no good programs were here, they lost the chance to continue or to replicate things that did work. I mentioned before that program for mentoring the next generation of principals that was so cost effective -- $3 million to run that a year versus $25 million to run the Leadership Academy.

When Rudy Crew was the chancellor, and also Harold Levy, they had this so-called Chancellor’s District, which were certain chronically ill-performing schools that would be under the direct oversight of the chancellor and that also tended to get a more phonics based English curriculum, language art curriculum in the lower grades, which was successful. Tossed out. Not continued.

"New York City is the envy of every other big city school system in the country."

Another example: When Rudy Crew went to Miami, he created with the teachers union there a program that could just as easily have been done here. Joel Klein talks about wanting to provide incentives, better pay, for teachers in the most hard to fill subject areas and then the lowest performing schools, and I think that is a great idea. What Rudy Crew has been doing in Miami -- and it’s also been done in Denver and a couple of other places -- is to agree with the union on a plan that says that a proven effective teacher, who will willingly go into a low performing school and work a longer school day will get more money. It won’t violate the union contract because that greater pay is pegged to the longer hours. That’s a way to keep harmonious relations with the union, to tap your most experienced people, to reward them – to incentivize, which is one of their buzzwords at the Tweed Courthouse – and they don’t do it.

I think there’s a sense that if they don’t come up with it themselves, it can’t have value.

Â