Although few people would see New York City as a college town, the truth is that the city has the most institutions of higher learning in the entire nation, as well as the most students -- and the most teachers as well. At least 25,000 academics teach about 425,000 students in the city's 57 colleges and universities.

These teachers do much for the city, not just educating the next generation of New Yorkers, but also enhancing the city's cultural reputation and strengthening its economy.

But what does the city do for them? As a whole, teachers of higher learning in New York earn less than the city's elementary school teachers. This helps explain some of the current turmoil in academia, with a strike by graduate students having resumed at New York University, and stalled contract negotiations between the administration of the City University of New York and the Professional Staff Congress, the 20,000-member union that represents the faculty and staff of the university.

It Doesn’t Pay To Be An Academic

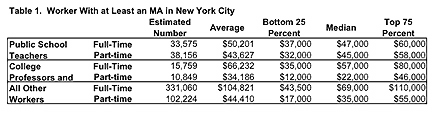

Table 1 (click here) lists most of the institutions of higher learning in New York City, with the numbers of students enrolled, the number of faculty, and their average salary. This varies widely. As a full professor at New York University, you could make $135,000; as an assistant professor at Boricua College, you could make under $35,000. But the truth is, more teachers make toward the lower end than toward the higher. The median income for full-time professors with at least a Master's degree is $57,000 – which is $3,000 less than the median income for all New Yorkers with Master's degrees.

And this is only the full-time faculty; there are no more than 16,000 people who teach full-time in New York at the university level. Another 11,000 who call academia their primary occupation nevertheless teach only part-time; their median income is only $22,000.

Put these two together and the median earnings in the year 2000 of New Yorkers whose primary occupation was academia (and who had at least a Master's degree) was $45,000 – or a thousand dollars less than the median income for elementary and secondary school teachers in the city.

And then there are the many academics who are forced to accept "adjunct positions," which often pay roughly $3,000 per course, or "visiting" (non-permanent) appointments, which also usually are not well paid. (Many of these teachers hold non-academic jobs as well.) In addition, many graduate students do some teaching while pursuing their degrees.

Public Versus Private

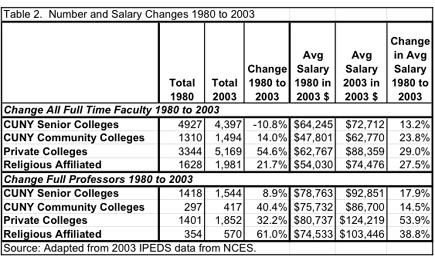

There are a wide variety of colleges and schools in New York City. Below, the "conventional" colleges are grouped into four types – City University senior colleges, City University community colleges, private colleges and religious-affiliated colleges – for the purposes of comparing both the number of faculty at each of these types of institutions, and their salaries.

As you can see above, both private and religiously-affiliated institutions of higher learning have overtaken the public university in many ways. While once salaries for full professors (the most experienced and the most sought after) at the senior colleges of City University were competitive with their peers at the private colleges, now they are far less; the ones at CUNY earn on average about $93,000, while those at non-sectarian private colleges in the city are paid an average of about $124,000.

In 1980, those teaching at religiously affiliated private colleges were earning about $75,000 (or four thousand dollars less than CUNY senior faculty); now they earn about $10,000 more per year. Given these data, it is not surprising that CUNY faculty members are severely discontent with their current salary. (For a breakdown college by college of the difference in number and salary of faculty members between 1980 and 2003, click here).

Academics are broadly representative demographically of others with a Masters or higher degree in New York City. Indeed, as Table 3 shows, the major differences between academics and others is that full-time academics have a lower household income than other full-time employed New Yorkers with at least a Masters degree, but other part-time workers live in households with lower incomes than those employed as part-time academics. Other part time workers are much less likely to be male.

Academics in New York City, especially part-time academics are struggling. New York City's large public university in no way is keeping up with the other four-year colleges in the city. Graduate students went on strike at NYU; there are grumblings at Columbia; many CUNY graduate students spend some time in the subway commuting from campus to campus. It is difficult to finish a Ph.D. program, where many students spend five, six, or seven years or more and roughly half leave without the degree . It is difficult to find an academic job, as the recent book Will Teach for Food graphically demonstrates . Swarthmore Professor Timothy Burke's very trenchant Web site "Should I Go to Graduate School?" spells out the perils of an academic career Yet, more academics are produced every year. New York City is still a place that many would be pleased to be if they could find a job, and afford to live here.

A Note on Sources

This column is based upon two sets of public data. The 2000 Census Public Use Micro-Data Samples (PUMS) from the IPUMS site and the Integrated Post-Secondary Education Data System (IPEDS), which includes data collected and maintained by the National Center for Education Statistics, but reported by the institutions. To find academics who worked in New York City, I used various codes from the PUMS data that depicted occupation, industry, type of employer and location of job. I limited my analysis to those with a Master's degree. For the data on colleges and universities, I selected those institutions that awarded at least an Associate Degree, but I did eliminate some that were trade schools or had recently lost accreditation, as well as those that were predominantly professional schools. There may be some differences in definition between 1980 and 2003, and I did not include fringe benefits, but the general patterns of change are robust.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and been in charge of Gotham Gazette's demographics topic page since 2000. The opinions expressed are his alone. Â