Much has been written about statistics showing that police "stop-and-frisks" in New York City are directed primarily at young African American and Latino males, but until now little attention has been paid to the link between those stops and a huge increase in marijuana arrests under the Giuliani and Bloomberg administrations. These arrests, like the stops, are skewed toward men of color.

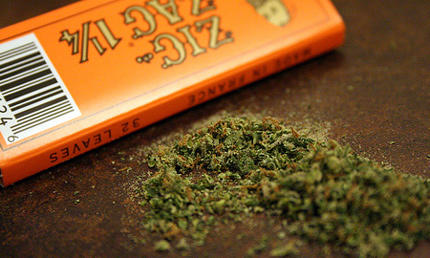

Between 1997 and 2007, New York City police arrested 353,000 people for possession of marijuana -- 11 times the number arrested during the previous decade, according to Harry Levine, a professor at Queens College, and Deborah Peterson Small, executive director of Break the Chains, a national group that sees the conduct of the "war on drugs" as a civil rights issue. In their 102-page report, "Marijuana Arrest Crusade: Racial Bias and Police Policy in New York City 1997-2007," they found that African Americans accounted for 52 percent of those arrested and Latinos for 31 percent -- even though reports have found generally higher use of the illegal weed by whites. Few other U.S. cities make marijuana arrests at these rates.

The report also found the police often tried to increase the charge from a violation to a more serious misdemeanor. The possession of seven-eighths of an ounce of pot or less is a violation punishable by a ticket and a $100 fine; a misdemeanor carries arrest and criminal charges. Police, according to the report, "typically discovered the marijuana by stopping and searching people, often by tricking and intimidating them into revealing it." That "kicked up" the charge from a violation to a misdemeanor for having marijuana "open to public view."

Creating Crime?

The misdemeanor charge means, the person arrested is handcuffed, photographed, fingerprinted, held overnight, arraigned in criminal court, plagued with permanent criminal records, and charged with the crime of having marijuana 'burning or open to public view," Nat Hentoff wrote in an article on the report.

This is "a humiliating, degrading, alienating experience," Levine and Small said. "The arrests create permanent criminal justice records which limit employment and educational opportunities."

Edward McCarthy, a legal aid supervisor in Manhattan criminal court, said he regularly sees the effects of the arrests. "Every day in New York City," McCarthy said, "many young men, mostly blacks and Hispanics, are arrested for possessing small amounts of marijuana. ... They are stopped by police, often as part of a stop and frisk, and are usually tricked or intimidated into taking out and handing over their contraband." Then, McCarthy continued, the young men spend the night in jail. "Legal Aid attorneys who work in the city's criminal courts see this every day," he said.

These arrests are expensive too. They "cost taxpayers up to $90 million a year," according to a release from the New York Civil Liberties Union.

The report attributes the explosion of arrests partly to the police desire for overtime. Levine noted the increase began under Rudolph Giuliani' second police commissioner, Howard Safir, whose background was in narcotics. "Morale was low in the department," Levine said, and the opportunity to make these arrests at the end of a shift was seen as "a way to fix the overtime issue." One of the report's recommendations is to pay police more so that they don't resort to these kinds of arrests to pad their checks.

As mayor, Michael Bloomberg continued the arrest policy -- even though Bloomberg acknowledged during his first mayoral campaign that he had used pot and liked it, a quote that a pro-marijuana group used in an ad campaign. The mayor's office referred requests for comment for this article to the police department.

The Police Response

In response to questions on the report, Paul Browne, deputy commissioner for public information, replied with an e-mail statement he had issued when the report came out earlier this spring. "The NYCLU has used an advocate for marijuana legalization to mislead the public with absurdly inflated numbers and false claims about bias," it said. (The Marijuana Policy Project, a pro-legalization group, provided some of the funding.)

Browne disputes the report's contention that most of the people arrested had only committed a possession violation. "The higher misdemeanor number was for individuals smoking marijuana in public and/or in possession of between 25 grams to 8 ounces of marijuana, not the 'few grams' that Levine described," he said.

Browne, however, refused to respond to question for more detail on this, despite repeated e-mails and phone calls. He would not, for example, provide information on what percentage of the misdemeanor arrests involved seven eighths of an ounce or less or respond to charges that police try to "kick up" the violations to misdemeanors.

He also did not provide a racial breakdown of the arrests. On May 30, a judge ordered the NYPD to open its database on stop-and-frisk arrests to the civil liberties union and other groups seeking to see them. This does not include the marijuana arrest figures.

Browne also said the report did not mention that these arrests decreased by 25 percent between 2003 and 2006. (Browne's complete statement is on a New York Times blog.)

Pot and Public Safety

In his statement, Brown said, "Attention to marijuana and lower level crime in general has helped drive crime down."

While no one disputes the need to address crime, some officials question whether the marijuana arrests represent a sound way to accomplish that.

"We have to make sure that we continue to live in a safe city," Rep. Anthony Weiner, a likely candidate for mayor, told Gotham Gazette. "But we also have to make sure that tensions between citizens and police are reduced and that police are making smart decisions. Some of the data raises questions about whether these [arrests] have been handled correctly."

"The NYPD routinely targets young men based on their skin color and where they live. Arresting and jailing thousand for marijuana possession does not create safer streets," said Donna Lieberman, executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Another likely mayoral candidate, City Comptroller William Thompson said he questioned "the huge disparity in the numbers of African Americans and Latinos arrested."

Maria Alvarado, a spokesperson for City Council Speaker Christine Quinn, said that disparity "raises concerns about racially biased policing" that she said "will be addressed by the council's Public Safety and Civil Rights Committees."

(Thompson, Quinn, and Weiner, by the way, all acknowledge past use of marijuana, Thompson and Quinn both saying their last time was "a long time ago," while Weiner's was in high school.)

Council Member Peter Vallone, Jr., chair of the public safety committee and a former prosecutor, expects to hold hearings in the fall on stop-and-frisk arrests including the marijuana arrests.

"I'm not going to jump to conclusions. Some facts are manipulated, especially by groups like the NYCLU," he said. Vallone said the number of blacks and Latinos stopped is not in and of itself an indication of racial bias. He explained that most stops are based on the identifications that victims of crime give to police, which is why, for instance, the vast majority of those stopped are male even though more than half the population is female.

He did question the misdemeanor charges, however. ""The police have every right to ask you to display what you have. You're free to say no. If, however, someone displays in response to a police request, it would be improper to charge them with displaying," Vallone said.

In the meantime, the civil liberties union is developing an advocacy plan on the arrest policy. To formulate it, the group will talk with district attorneys and elected officials and try to obtain additional data, according to Jennifer Carnig, director of communications for the New York Civil Liberties Union. "The report was just the first step--an effort to shine a light on this issue," she said in an e-mail.

Levine believes that public officials will have to become involved in the next step. "Police Commissioner [Ray] Kelly and other top officials at the police department, who have directed police officers to make these arrests, are unlikely to change NYPD practices until pressured to by the City Council, the State Legislature and other officials," he said.

Such changes cannot come too soon in the view of Norman Siegel, a civil rights lawyer and likely candidate for public advocate. These arrest "are too often unconstitutional and they have a ripple affect on the city in increased alienation and disrespect for law. We need to confront these issues sooner rather than later, including opening up discussions with the NYPD."

Andy Humm, a former member of the City Commission on Human Rights, has been in charge of the civil rights topic page since its inception in 2001. He is co-host of the weekly "Gay USA" on Manhattan Neighborhood Network (34 on Time-Warner; 107 on RCN) on Thursdays at 11 PM. Â