Central Park at 150

.........................

Overview:

Still a Pioneer

Art in the Park:

Our Project for the Park by Christo and Jeanne-Claude

History:

» Birth of the Park

» Death of Seneca Village

My Backyard:

» Dancing in the Park

» An Escape from Reality

Crime:

Taking Back the Park from Crime

Reading:

Books About Central Park

Turning Manhattan swampland into Central Park’s vast acres of woodlands, meadows and ponds took16 years and cost $14 million. But building Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’s “Greensward Plan” was not without a human cost as well. More than 1,600 people were displaced by Central Park, including Manhattan’s first known community of African-American property owners, Seneca Village.

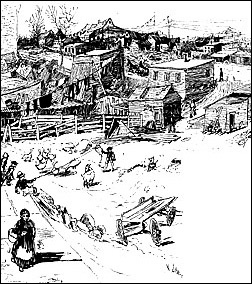

From 1825 to 1857, Seneca Village was located between 82nd and 89th Streets at Seventh and Eighth Avenues. The New York State Census of 1855 reported that 264 people, largely African-Americans but also Irish and German immigrants, lived in Seneca Village. By the time it was destroyed, the village had grown to include three churches, a school and several cemeteries.

There are many theories about how Seneca Village got its name, according to the New York Historical Society: it could have been named for the Seneca tribe of Native Americans, or a distortion of the word “Senegal,” where many of the village’s residents may have come from. It also may have been a code word used by Underground Railroad fugitives, or named in homage to Roman philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, whose book Seneca’s Morals was popular among African American activists.

The community was founded on September 27, 1825 when an African American former boot black named Andrew Williams bought six lots of land for $125, and another African American laborer, named Epiphany Davis, bought 12, for $578. The trustees of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church purchased six lots of land on the same day.

Buying property in Seneca Village was relatively inexpensive compared to prices downtown, and by 1850, African Americans in Seneca Village were 39 times more likely to own property than African Americans in other parts of the city. This made them more able to participate in civic life -- at the time, the New York State Constitution of 1821 required that African-American males had to own $250 in property in order to vote.

In 1853, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church built a church in Seneca Village, and, according to a newspaper account of the time, church officials laid a special cornerstone that contained a Bible, a hymn book, the rules of the church, copies of the New York Tribune and the New York Sun, and a letter with the names of the church’s five trustees.

The new church would not stand long enough for the cornerstone’s contents to become more than a few years old. The state legislature set aside the land for Central Park in the same year that the church was built. During the 1850s, newspaper articles described Seneca Village as “Nigger Village.” The New York Daily Times wrote on July 9, 1856, about Seneca villagers, “The policemen find it difficult to persuade them out of the idea which has possessed their simple minds, that the sole object of the authorities in making the Park is to procure their expulsion from the homes which they occupy.”

The government used the power of eminent domain to force the people of Seneca Village out of the area, giving them the final notice to leave in the summer of 1856. Those who owned property were compensated, but many fought to keep their land or get a better payment. The residents of Seneca Village did not re-establish their community in another place, and instead scattered throughout the city.

The story of the village that was destroyed to make way for New York City's great park went largely untold until recently, and it was not until 2001 that the Central Park Conservancy put a plaque commemorating the lost community in the park.