There is no doubt that from 1991 through 2002 New York City experienced a remarkable drop in crime. From an analysis(PDF Format) presented at a conference in Italy by two US Department of Justice statisticians in late 2003, one can see that no matter how one looks at it, crime dropped massively in New York City. Yet the popular explanation for the decline, favored by a former police commissioner and a former mayor and many crime specialists, no longer seems as convincing as it once did. How can we be sure that the "reported crime rate" is the real crime rate? More importantly, how do we know if the crime rate is truly dropping and how fast it is dropping?

Recently, Newsday uncovered some false counting of certain crime incidents in one precinct, while the police union claimed that the continuing decline was suspicious in light of some staffing reductions. The city dismissed these charges. (Read a discussion of this on Gotham Gazette's crime topic page.) This controversy points up a fact well known to those who deal with crime statistics: the "official crime" rate depends on crimes being reported to the police by the crime victims and accurately recorded.

GAUGING THE DROP IN CRIME

The FBI through their Uniform Crime Reportingsystem keeps track of crime statistics for eight selected offenses: 1) murder and non-negligent manslaughter 2) forcible rape 3) robbery 4) aggravated assault 5) burglary 6) larceny-theft 7) motor vehicle theft, and 8) arson.

Each police jurisdiction throughout the United States, including New York City, submits periodic data that gives reported crimes and arrests in these areas. Data from this system form the raw material for comparing crime rates in the major cities, and for tracking reported crime nationally.

Most crimes remain unpunished, and many remain unreported. This fact makes measuring crime very difficult. Complicating the matter further is the fact that the "official reporters" of crime statistics are those charged with finding and catching offenders, the police forces themselves. Often there is pressure to have a lower crime rate, which can cause crime to be unreported or reclassified. Murder, of course, is a special case. Most murders do end up being reported to the police. Also since murder results in death, each murder also creates a vital statistics record. Reporting of other crimes varies greatly. Petty thefts often go unreported. Some muggings, assaults and rapes also remain unreported. Automobile theft, because owners need the police report to make a claim is much more likely to be reported.

Researchers knew for years that much crime goes unreported to the police, while some police departments may be better at reporting crime than others. For these reasons, the US developed a measure of crime independent of police reporting. Since 1973, the Bureau of Justice Statistics has conducted a "crime victimization study," where residents 12 or older are asked to describe crimes for which they were the victim. New York City is one of the 12 cities where a special local survey is done.

COMPARING OFFICIAL AND SURVEYED CRIME

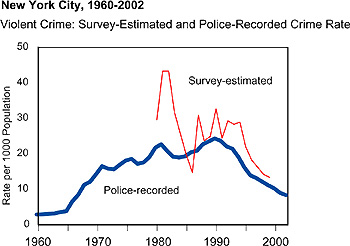

For New York City it is possible to compare official crime statistics with survey results for several years. The accompanying charts present data for property crime and for violent crime based upon both official and survey statistics. Looking first at property crime, in New York City the number of property crimes reported by the survey is much greater than that reported to the police. Indeed, in some years it is several times greater. Both the reported crime and the surveyed crime show a marked decrease in the 1990s. When one looks at violent crime one sees the same marked decline. However, a much higher proportion of violent crime than of property crime is brought to the attention of the police.

Not only has New York City's crime drop been significant and sustained, it also is corroborated with the decline in the crime survey. For murders, the decline is mirrored by that for homicide reported through the vital statistics system. New York City is now the safest large city in the US, the one with the lowest crime rate.

EXPLAINING THE DROP

Former Commissioner William Bratton and his late deputy Jack Naples along with former Mayor Rudy Giuliani had a ready explanation, their implementation of strategies based upon the so-called "Broken Windows" theory. The theory has been one of the most important in criminology. It was first proposed in an article published 20 years ago in The Atlantic Monthly, written by Dr. James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. The theory provided the intellectual foundation for a crackdown on "quality of life" crimes in New York City. Today, "broken windows" policing is endorsed by police chiefs across the country, its proponents sought out for lectures and consulting around the world. (Several books taking various perspectives are mentioned in Gotham Gazette round-up of crime books.)

Recently, this theory has been seriously challenged by a rigorous studycosting over $50 million carried out in Chicago by Professor Felton Earls of Harvard, and his fellow researchers, Robert Sampson also of Harvard, Steven Raudenbush of the University of Michigan and Jeanne Brooks Gunn of Columbia. Earls and his colleagues argue that the most important influence on a neighborhood's crime rate are neighbors' willingness to act, when needed, for one another's benefit, and particularly for the benefit of one another's children. And they present compelling and rigorous scientific evidence to back up their argument. "It is far and away the most important research insight in the last decade," said Jeremy Travis, former director of the National Institute of Justice. "I think it will shape policy for the next generation." Many find their work controversial. One of their original articles was attacked on the floor of Congress, while winning several prestigious awards by professional associations.

Dr. Wilson recently conceded that the "broken windows" theory lacked substantive scientific evidence that it worked. "I still to this day do not know if improving order will or will not reduce crime," Dr. Wilson, now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Los Angeles, recently told the New York Times. "People have not understood that this was a speculation." So crime continues to decline in New York City as it has for more than a decade, but we still do not know the reason why.

Andrew A. Beveridge has taught sociology at Queens College since 1981, done demographic analyses for the New York Times since 1993, and provides expert testimony on a range of cases, including housing discrimination. The opinions expressed are his alone.