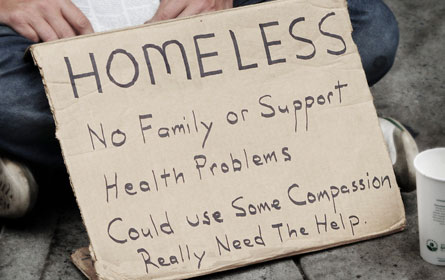

When a group of battered women and homeless individuals and families, agreed to leave public shelters and become tenants of private but rent subsidized apartments offered by the City of New York, they expected to occupy them for one to two years. The City was to pay all or a portion of each unit’s rent for one year and renew for a second year if the occupant met the eligibility requirements for the Advantage Program, including that they fulfilled public assistance requirements and worked 20 hours a week at minimum wage jobs. However, the Program ended soon after it began when federal and state funds were cut off. And the formerly homeless and victimized faced homelessness and violence once more.

A lawsuit against the City of New York sought continuation of the Advantage Program. But trial judge Judith Gische dismissed the case, finding that there was no contractual promise to provide the apartments. Last month that decision, known as Jasmine Zheng v The City of New York, was upheld by the Appellate Division of the New York State Supreme Court in Manhattan. Saying, "We sympathize with plaintiffs and realize that an adverse outcome places them at risk of again ending up in the New York City emergency shelters… ," the four judges agreed that "defendants [City] are not contractually obligated to continue making rent subsidy payments under the Advantage Program."

What was the relationship between the shelter occupants and the City when the moves from shelter to individual apartments took place? "Simply social services," said the judges. With one judge dissenting, the Court held that making apartments available to people who gave up their places in homeless shelters was "simply social services and the defendants did not intend to be bound contractually."

An Opinion by four of the five judges who heard the appeal, held that "the existence of a binding contract is not dependent on the subjective intent of the parties, but on the objective manifestations of intent." The City argued, and the Court accepted, that the signatures on City-prepared documents were only to "ensure that the participants were aware of the terms of the program." In other words, the signatures on a document and the use of such words as "agree" and "guarantee" did not mean it was an agreement or a contract, and the tenants simply did not understand that it was within the City’s discretion to terminate; there was, the judges ruled, no "meeting of the minds," an essential element of a contract.

Since there was no contract, there was no obligation to continue the rent subsidy. The Court rejected tenants’ argument that they gave up something – places in shelters – for the subsidized housing, seeming to say they would have had to do that whenever so directed by the City, anyway (despite the obligation to provide housing accomodations), meaning that they really gave up nothing. The plaintiffs’ argument that they were induced to leave the shelters to move into into apartments they could not afford without the subsidy, was also found to be "without merit.

While four judges concurred, only Justice Karla Moskowitz dissented, finding that the plaintiffs were induced to leave the "relative safety of the shelter system and to enter into leases for apartments they could not afford [without public subsidies]." She found that there were enforceable contracts under which the "city agreed to pay plaintiffs’ rent in return for plaintiffs leaving the shelter system." The rent payable to the landlord was, according to Justice Moskowitz, a commitment not only to the residents, but also to the private landlords the city would be paying on their behalf. Analyzing the legal elements of a contract, she found that the agreements were, in fact, binding contracts even if they were also part of a "social benefit program." In addition, she said that the written documents prepared by the City and signed by the plaintiffs, described itself as an "agreement." The participants then signed leases with private landlords with the City paying the Advantage portion directly to the landlord. The agreements stated that the City was paying the rent in return for the plaintiffs leaving the shelters and said, the "Advantage program guarantees that the subsidy portion of the rent will be paid ..." The conditions that the participants remain eligible was never breached by them and the only condition for continuing the program into the second year was that on-going eligibility. Most telling for the dissent was that the City never conditioned the program on the continuation of state or federal funds and that the City concedes that it is less costly to fund the Advantage Program than to house plaintiffs in shelters, and that continuation would not only mean honoring a contract, but would save the City $133million.

Disagreeing with her colleagues, Justice Moskowitz describes their Opinion as a "red herring," and "buying into" the argument that "plaintiffs had a legal obligation to seek housing anyway." But, she argues, they had "no preexisting obligation to move into apartments they could not afford on their own. Nor did plaintiffs have an obligation to place themselves in a worse situation than they were [in] before." This left them legally bound to leases they "could not afford on their own." Parsing the language of the documents, the dissent refers to the City’s chosen words: guarantees, shall pay, will pay, assures, commitment as demonstrating "an intent to bind oneself contractually."

Seeking apartments for themselves at the beginning of the process, the would-be tenants had to show private landlords the documents prepared by the City and the landlords undertook the leases containing language that "the City ... will pay directly to me, the Landlord, monthly rent .. .’" These the dissent said, constitute a clear "assent to guarantee rent payment....." Judge Moskowitz said that the trial judge who dismissed the case was incorrect in finding that the landlords did not manifest assent when, they agreed to accept the tenants, and to continue the tenancies for a second year based on the City’s determination of eligibility, and agreed not to raise tenants’ rents, and forego other property rights in exchange for guaranteed rental payments for one to two years. This, Justice Moskowitz calls, "a textbook example of mutual assent." Also, the landlords would be unable to collect rent from tenants who never had the ability to pay the rent on their own, and would have the burden and expense of undertaking eviction proceedings which they never bargained for in dealing with the City. With the majority upholding the Gische decision, the tenants would be left with apartments they could not afford on their own, and the prospect of homelessness. Those who were victims of domestic violence, would lose not only their places in shelters, but also the protections against their abusers. "...they may be forced to return to the dangerous homes they sought to escape in the first place. Some may simply take to the streets," concluded the one judge who would have upheld the agreement as a binding contract

The judges in the majority were Justices Gonzalez, Sweeny, Renwick, Richter.

In addition to the actual parties, amicus curiae (friends of the Court) briefs were filed by Sanctuary for Families, New Destiny Housing Corporation, Center Against Domestic Violence, Safe Horizon, Violence Intervention Program, In., New York Asian Women’s Center, Good Shepherd Services, Barrier Free Living and Homeless Services United.

The plaintiffs were represented by The Legal Aid Society and Weil Gotshal and Manges LLP.The City of New York was represented by Corporation Counsel. The Amicii were represented by Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP.

Emily Jane Goodman is counsel to Siegel Teitelbaum & Evans, LLP