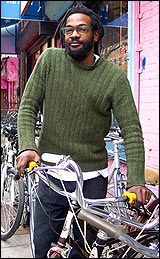

Three teachers who left the city's schools tell their stories.  Christina Young Christina Young  Michael Burns Michael Burns  Daniel Ginsberg Daniel Ginsberg |

Nevertheless, a year later, Burns quit.

Every year, more than 11,000 of New York City's 80,000 public school teachers stop teaching. Some simply retire. Others, like Burns, get fed up.

Indeed, according to the United Federation of Teachers, 45 percent of all New York City teachers either quit the profession entirely in their first five years on the job or leave for a teaching position outside the city public school system.

The loss puts a strain on the city, which is burdened with a constant demand for new recruits (and the money to lure them). It also puts many students at a disadvantage. Not surprisingly, studies have found teachers become more effective after they have a few years of experience. One study concluded that students whose teachers had five years of experience made as much as 30 percent more progress in reading skills than those taught by first-year teachers.

In New York, the city's poorest children are the most affected. Their schools exhibit the highest turnover rates, they are taught by the least experienced teachers, and with few exceptions, they score lower on math and reading tests than their more affluent peers.

The grim economic outlook makes it unlikely that the city will battle the high turnover with what is generally considered to be the most effective tool: pay increases. Though the teacher's contract signed last summer provided a 16 percent across-the-board raise, it expires this spring, and with hundreds of millions of dollars in education cuts looming with a budget deficit in the billions, the city will be hard pressed to provide any more substantial raises.

The good news is that money isn't everything. According to Richard Ingersoll, of the Center for the Study of Teaching Policy, teachers are less likely to leave their jobs – no matter how poor their students – if their school offers them:

| • | Strong administrative support during their first two years on the job |

| • | Involvement in school decision-making |

| • | A well disciplined student body |

Meanwhile, three teachers who quit explain why.

-- Yaniv Nord

Focusing on Appearance

By Christina Young

I taught fifth grade at P.S. 65 in the Bronx for two years, and I believe that if my administration had been different I would have stayed longer.

I taught fifth grade at P.S. 65 in the Bronx for two years, and I believe that if my administration had been different I would have stayed longer.

My first week, I arrived to 33 fifth graders in my classroom and not enough desks. I had a kid banging his head against the closet, one who ran away, one who hid under a table for an entire day, one who cursed at me. In all the cases, I called down to the office for assistance, and no one ever came up. A gym teacher who had been in the school for 17 years was placed in my classroom, but he just sat in the back and slept.

Eventually, a veteran teacher came to me and said, "When you need something, ask me, because the administration is never going to help you."

One of my main frustrations with the school was that I had chosen to teach at P.S. 65 after being told by the principal that her focus was on the kids, but in reality it was on the appearance of success and order, and on standardized tests.

I once got a phone call saying, "The superintendent is on the way up, take out "Success For All," a reading program that my class hadn't touched in weeks. When the superintendent arrived, we pretended to be working on the program. The kids, of course, knew exactly what was going on. It was horrifying.

Another time, there was a principal's conference in our school, and we were told to skip six weeks ahead in our math lessons in order to create the illusion of being on schedule.

The focus on appearance affected everything. A favorite topic of faculty meetings, for example, was the state of our bulletin boards. Charts, we were told, had to go up. Charts had to come down. Projects needed to be hung. Boards needed to have themes. Boards needed to match by grade. If your kid wrote a five-page paper that was going up, there could be no errors. New bulletin boards had to go up every 3.5 weeks. In my first year, I was publicly reprimanded for the appearance of my bulletin boards and would receive notes on the general state of my classroom.

Never once, however, was I asked about the projects we were working on, about the books my kids made, the poems they wrote, the food and clothing they saw when we studied westward migration, or the computer presentation they had created after I snuck them into the technology lab. My room had projects hanging from the lights, things to read, things to touch, work that the kids had made. It was exciting, it was ours, and we were so proud of it, but all my principal could say was, "Now, look around here, is this really as neat as it could be?"

In a school that averaged 18 to 23 percent of students at grade-level, 50 percent of my students were on track after my first year. I am not sure what all the factors that lead to this were, but I went from being the administration's she-devil to being praised in public in front of all the other teachers. Earlier in the year I had been yelled at during staff meetings and was told that I had failed my kids.

During my first year, I spent $5,000 of my own money on special project materials, museum trips, IMAX movies and books. I'm currently being audited by the Internal Revenue Service for declaring it as a business expense.

Christina Young was a New York Teaching Fellow from 1999 to 2002. She is now studying law and hopes to one day get involved in education policy.

Products of a Broken System

By Daniel Ginsberg

When I used to tell people in New York that I was a teacher, they responded as if I did volunteer work. If I had made more than $30,000 I might have argued with them.

My first year I made $29,800. I started late in October and was already the fifth science teacher my students had had that year. I did not teach a violent population -- they weren't bringing knives into the school or anything -- but they were tough, neighborhood kids who had grown up in New York City in the height of the crack epidemic. Some of their mothers were addicts; some had lived in homeless shelters. I had kids who were living in domestic abuse shelters. It was a tough population.

The kids I taught, as I saw it, were products of a broken educational system, and they were not prepared for classroom work. I felt like I had walked into a situation where I had to do eight years worth of teaching in one semester. It was a daunting task. The feeling I got was, "Do the best that you can with these kids," rather than, "Make these kids excel."

But that was the reality. You can't teach eighth grade kids about molecules when they read at a third grade level. You can't teach chemical equations if they don't know how to add. I was constantly getting to a point in my lessons, walking three miles back and then slowly returning to the starting point.

In my first year, I spent nearly $1,000 out of my own pocket. The science class had no supplies, not even the basic tools of measurement. I would buy magnifying glasses at dime stores, posters for the walls, clay to build things. We raised a lizard in the classroom, so every week there was lizard food to buy.

Also, I scavenged. Anything that I found, I brought to my classroom. I had closets full of junk. When kids got into trouble, I would have them organize it. In my physics class we were studying electricity, and out of soda bottles, wood, electric tape, nuts, bolts, miniature engines that I pulled out of things in the street, we made cars and boats that worked, with chopped up compact disks as propellers. Out of soda bottles, cotton puffs and balloons, we made molecules.

I would wander around to all the elementary school classes and ask for their stuff. I was a beggar. You got any crayons? You got any straws? And they knew that when I came around, they should start digging in their closets. But we built a greenhouse out of stuff I had scavenged.

What would have kept me in this job? If my master's degree had been paid for, I would have stayed, and if I was making a salary that was even remotely in line with the difficulty of the work I was doing, I would have stayed.

Daniel Ginsberg taught science at P.S.51 in Hell's Kitchen from 1996 until 1999. He now develops computer programs used by school districts across the country.

Discouraging Curiosity

By Michael Burns

Teaching is a life experience. From my first breath in the morning, to my dreams when I slept, it affected every part of me. I left, in the end, because I was completely burned out on the futility of the model that we use.

Teaching is a life experience. From my first breath in the morning, to my dreams when I slept, it affected every part of me. I left, in the end, because I was completely burned out on the futility of the model that we use.

When I got my first assignment, the administration was just happy to have someone to keep the kids in the room. It was a complete throwaway class -- 18 kids with disciplinary problems bad enough that the school had decided they were too disruptive to be in regular classes. So they took them and put them all in one room, and because these kids were deemed "problem kids," they didn't get to move from class to class and subject to subject. I taught all subjects to them. It was ludicrous -- I was originally hired to teach math.

The kids fought, they cursed, they punched lockers, they spit on me, but I came to understand they acted in that way because all the messages they had received up until that point had told them to. They were just a reflection of their society at large. It wasn't their fault that public education was a mess.

The system discouraged intellectual development. It wanted rote answers, wanted everything to be nip and tuck, and as a result our lessons disregarded the "Why?" of learning. Intellectual curiosity and intellectual investigation had been completely removed. We had 44-minute teaching periods, split sessions, average class sizes of 33, terrible food in the cafeterias and completely confusing bell schedules.

By my third year, I was teaching my students out of an old college statistics textbook. I had them put their books away and photocopy pages out of mine. We developed hypotheses, collected data, plotted graphs and started to actually do research and case studies on other classes in the building. These were eighth graders who were going out and doing sociological and statistical inquiry --- just because I told them that they could, and so they believed that they could.

Everybody can learn, it's just a matter of the model adapting to them rather than them being forced to adapt.

In the end, I left because I couldn't grow to be the type of teacher I wanted to be in that environment. The public school system was too closed, too insular, too regimented and too standardized.

To be a good teacher is so much more than to stand up in front of a classroom. There is the saying "Those that can, do, and those that can't teach." That resonated with me the third year. I thought, "I don't know enough, I'm not mature enough, I have not experienced enough raw living to be able to stand in front of a classroom of kids and teach and be able to understand where they are coming from." And the public school system was too insular a place for me to gain that experience.

After I left the Board of Ed, I started working at Project Green Hope, which is a residential treatment program for drug addicted women, an alternative to incarceration. I went in and wrote a high school equivalency curriculum for them from scratch, and it is still being used.

Now, I am working in a bike shop in Brooklyn, playing music with a number of bands, I have gotten married and just had my first kid. I have started teaching again, too -- part time, at one of the city's welfare-to-work programs. I teach Adult Basic Education and General Education Development.

Michael Burns taught mathematics at I.S.90 in Washington Heights for three years. Originally from Arkansas, he arrived in New York City with Teach For America's class of 1996.