The financial meltdown and the recession have thrown state budgets out of whack across the country. Plummeting revenues have given New York State a projected budget gap of $1.7 billion for the current fiscal year and $13.7 billion for the new fiscal year that will begin April 1. The combined deficits of New York and 45 other states through 2010 are predicted to reach a staggering $350 billion, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Meanwhile the recession is taking a toll on people across the state. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers have lost their jobs, their homes or their hopes for a secure retirement or a better future for their children. New York's unemployment rate jumped by a full percentage point in December to 7 percent, the greatest one-month increase on record since 1976. The state has lost 121,000 jobs since its August 2008 job peak. More than 50,000 New Yorkers lost their homes through mortgage foreclosures last year.

As the economic damage ripples out from Wall Street, Gov. David Paterson has proposed drastically slashing state spending. School aid, health care, SUNY and CUNY, child care, program for the elderly, homeless prevention and long-overdue wage increases for social service workers struggling to stay above the poverty line will all feel the effects of the budget ax. While he chops away, though, the governor has steadfastly refused to call for a progressive hike in the state income tax -- an increase that would affect only the most affluent New Yorkers.

For the governor, "shared sacrifice" means that the state's low- and moderate-income families and communities must sacrifice while the fortunate few at the top, who benefited the most from the tax cuts of the last 15 years and from this decade's economic growth, will emerge from the budget largely unscathed.

Too Much Spending -- or Too Little Revenue?

Anti-government voices have mounted a steady drumbeat calling for steep budget cuts, ostensibly to rein in "out of control" state spending. The reality? State spending has increased to fund important new commitments such as providing medical care to people without health insurance and aiding urban school districts with high concentrations of children from poor families. The state government also dramatically expanded spending on property tax relief and acted to partially undo years of underinvestment in mass transit and public higher education.

Aside from these major commitments—all supported, by the way, by David Paterson when he was a state senator and lieutenant governor--state spending from 2004 to 2008 grew at less than 2.9 percent a year, barely the pace of consumer inflation.

What the state failed to do, however, was provide the revenues needed to finance such initiatives through the ebbs and flows of the business cycle. Much of the state's current budget crisis might have been averted had the state reversed even part of the tax-cutting spree carried out from 1994 through 2000. All tolled, these cuts now reduce the state's tax revenues by about $20 billion a year, an amount that would erase even the huge projected budget gaps of $17 billion for 2011 and 2012.

Less Pain, More Gain

Like the other 49 states, New York has to balance its budget in both good times and bad. Facing a sizable budget gap during a recession, states have only bad choices. Neither cutting spending nor raising taxes eases the downturn.

Many economists, however, point out that it is less harmful to the economy to raise taxes in a way that limits its effects largely to high income people than to cut state spending that mainly benefits low- and moderate-income people or that pays the salaries of teachers, police officers and other civil servants. In December, 120 economists from across the state sent a letter to Paterson saying, "Economic theory and historical experience [show] it is economically preferable to raise taxes on those with high incomes than to cut state expenditures."

This is because high earners typically spend only a fraction of their incomes in any given year, saving the rest. On the other hand, state spending goes to pay workers, provide services and put money in the hands of New Yorkers in need. This means the money goes directly into the economy, priming the pump at a time when it is desperately needed. Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz of Columbia University made the same point in a letter to the governor last March.

Public opinion across the state strongly favors increasing income taxes on high earners over cutting spending for health care and education. The governor, though, has argued that raising taxes on the wealthy will drive them from the state.

No evidence exists to support that claim. In 2003, New York temporarily raised its top income tax rate from 6.85 percent to 7.7 percent. During the three years that this increase was in effect, the number of high-income returns grew significantly. This experience in New Jersey, which permanently raised its top personal income tax rate to 8.97 percent in 2004, has been similar, according to a Princeton University study.

Beyond a High-End Tax Hike

Paterson and the two top legislative leaders -- Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver and Senate Majority Leader Malcolm Smith -- have committed to closing the projected $1.7 billion budget gap for the current fiscal year by Feb. 4, even though the year does not end until March 31.

What should they do? In addition to its investments in infrastructure, unemployment insurance modernization and other measures, the massive economic recovery bill now making its way through Congress includes aid, called “state fiscal relief,” for the explicit purpose of helping states balance their budgets without putting too much additional drag on the economy. Since this legislation is likely to go to President Barack Obama for his signature in mid to late February, the sensible course would be for Paterson and the legislature to wait to see exactly how much “budget balancing” aid New York will receive under the final legislation. The chances are excellent to certain that the state will get several billion dollars it can use right away, since important parts of the “state fiscal relief” is retroactive to Oct. 31, 2008.

In the unlikely event that the immediate “state fiscal relief” does not close this year's gap, the governor has already identified at least $600 million in various reserve funds that could be tapped to balance the books. On top of that, the state has at least $1 billion in its Tax Stabilization Reserve Fund that it could us if needed. Even if it had to borrow against that -- which seems unlikely -- the state still has $400 million in a newer "rainy day" fund as well as a few hundred million in other reserves.

Closing the projected $13.7 billion gap for the 2010 fiscal year will prove more difficult. A progressive tax increase would generate roughly $5 billion. This, along with several billion more from an increase in the federal payments for Medicaid or state fiscal relief in the stimulus package will address most of the budget gap.

Some budget cuts may be unavoidable, but the state should also consider closing tax loopholes such as one that benefits non-resident hedge fund general partners working in New York State and taking other actions to generate budget savings. These could include ending the wasteful and failed Empire Zones program, increasing the use of state engineers rather than contracting out that work to expensive consultants, or using the state's sizable purchasing power to get better prices on prescription drugs.

Restoring Tax Fairness

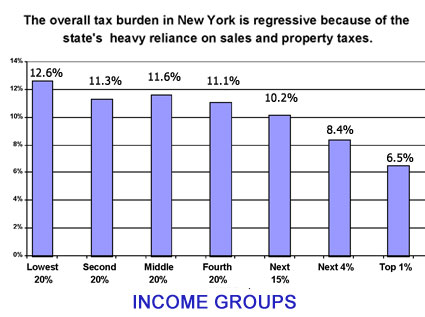

Raising taxes on high earners would also be a step toward restoring fairness to New York's graduated income tax, which has become significantly less graduated over the years. Today, because of the state's increased reliance on regressive sales and property taxes, New York's middle- and lower-income households pay a higher share of their incomes in state and local taxes than the top 1 percent or the top 5 percent (see chart).

Moreover, as astounding as it may seem, data indicate that all of the income growth in New York State from 2002 to 2009 has gone to the wealthiest 5 percent. In 2009, the other 95 percent of households have roughly the same incomes they had in 2002. When you factor in inflation, the combined income of the bottom 95 percent of New Yorkers actually shrunk.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman recently wrote in his New York Times column that, in the absence of Obama's massive stimulus proposal, we might see 50 Herbert Hoovers in state houses across the country respond to revenue shortfalls by slashing their budgets or raising regressive taxes, making the economy worse in the process. The new stimulus program is designed, in part, to head off that result. For the part of the budget gap that cannot be closed through federal funds, the state should turn to progressive tax policies. This is the right economic policy, sound fiscal policy, and the only approach in keeping with the governor's theme of "shared sacrifice".

Frank Mauro is the executive director of the Fiscal Policy Institute. James Parrott writes a regular column on the economy for the Gotham Gazette and is FPI’s deputy director and chief economist.